The State of Police Reform: What has and hasn’t changed in St. Louis policing?

Download the “State of Police Reform”

Read Board chair Rebeccah Bennett’s remarks during the report’s press conference

For the second installment in our State of St. Louis series, we have completed an in-depth exploration of changes made in the law enforcement space. Called the State of Police Reform, we set out to answer three core questions about police reform since the killing of Michael Brown and release of the Ferguson Commission Report.

- What has changed? What police reform calls to action have been implemented?

- What factors have facilitated change?

- What factors have held it back?

“We need to be clear about our goal: to set a new culture and climate for public safety that is deeply committed to building a healthy and thriving community. This is fundamentally different from a vision of policing that focuses on law and order without a clear understanding of the root causes of violence and crime, which have just as much (if not more) to do with the structural drivers of poverty, limited options, and divestment as they do with individual decisions and behavior. Diagnosis determines treatment.” –State of Police Reform

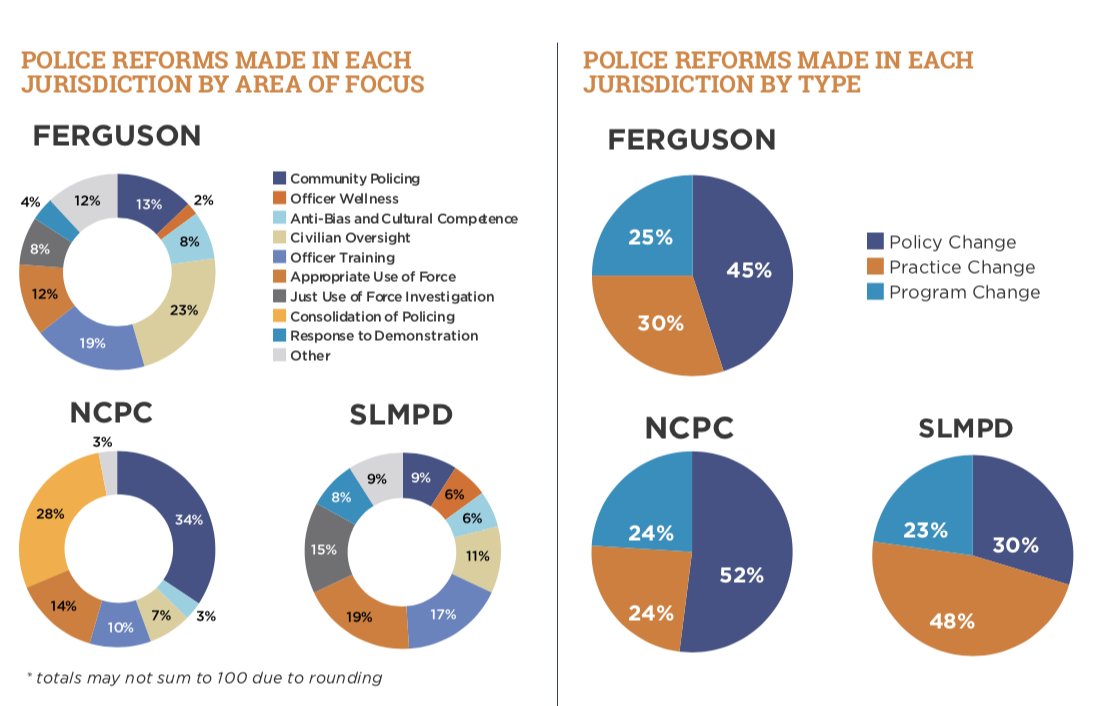

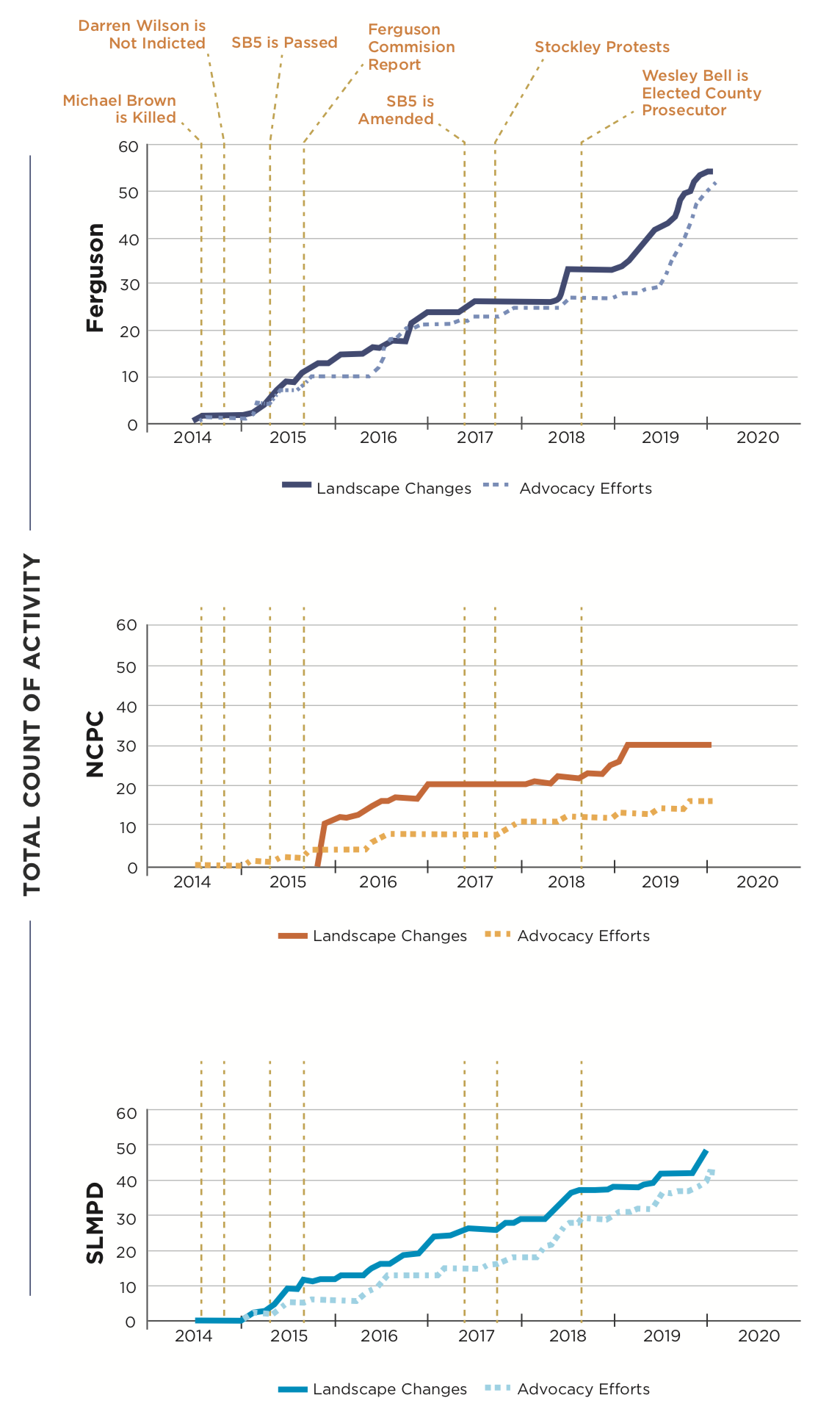

We choose three police departments (Ferguson Police Department, North County Police Cooperative, and St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department), conducted 57 conversations with key stakeholders both inside and outside the departments, and documented 288 events. However, we saw three fairly different narratives of reform when we looked at timecourse graphs for each department.

Total count of activities documented in each of the three police departments.

In Ferguson, we saw how reform can be facilitated by a legal mandate like the Consent Decree. We also saw how the restrictive procedures of that mandate can also slow things down. In addition, Ferguson was an eye- opening example of extreme volatility in leadership (seven chiefs in five years) and how that degree of upheaval can impede reform.

The birth of the NCPC was a story of growing more organically from community-oriented roots catalyzed by strict accreditation standards and regional demands for change.

SLMPD’s size led to particularly complex dynamics including a larger leadership structure (e.g., mayor + chief + public safety director) that often precluded a strong, consistent, and clear commitment to one

platform; a nearly constant flux of legal action both spurring and slowing change; and an oftentimes

oppositional police union.

Our interviews showed that areas of progress across all departments include establishing internal use-of-force databases and increasing police training hours. Neglected or challenging areas of change for all departments include improving officer wellness and ensuring appropriate use of technology.

The report also discusses disparities in policing, courts, education, healthcare, housing, and income and how those disparities—disproportionately borne by Black people, family, children, and communities—cost the entire St. Louis region. In fact, the St. Louis Region lost more than $17 billion due to racial disparities in income. The report concludes with the results from a survey we circulated at two points, 2016 and 2019. We found that most people do not feel like much has changed, a result that necessitates a conversation on why the outlook is so dismal.

“So, we close with the uncomfortable fact that progress is small, and can seem excruciatingly slow, and beset by failed and superficial attempts. But it’s here. Change is happening, and that means we can learn from it, and try to do better moving forward.” –State of Police Reform