Folks have to know that you’re there and you’re working on their behalf. This is part of the #STL2039 Action Plan storytelling series in partnership with Humans of St. Louis.

Jamala Rogers: I’m the Executive Director and one of the founding members of the Organization for Black Struggle. At this point of my life, I’m a lot of different things. When I was younger, I was going to be a change agent. I thought that would happen in a couple of years because if it was matching my enthusiasm it was going to be done like that! And here we are some 50 years later still doing that work. So I’ve got an appreciation of how long it takes for change to happen. Doesn’t mean I’m satisfied with it. But, I think that. I always tell people, “Change could happen quicker and be more substantive if there are more people doing it.” That little thing about, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world…” No, this is the world and this is a country that needs lots of people engaged in a meaningful way. That’s the only way that change is really going to happen.

I’ve got an appreciation of how long it takes for change to happen. Doesn’t mean I’m satisfied with it. But, I think that.

I’ve been an organizer, I’ve been a storyteller, I have a column in the St. Louis American, and I’ve been doing that for almost 25 years. I’m seeing and hearing folks’ stories, and I’m actually a part of their lives because I’m organizing. And some of those folks are involved in that organizing around issues that impact them. I am a change agent, a facilitator, a mediator, a listener, an author. You have to be all of those for real to appreciate transformative change.

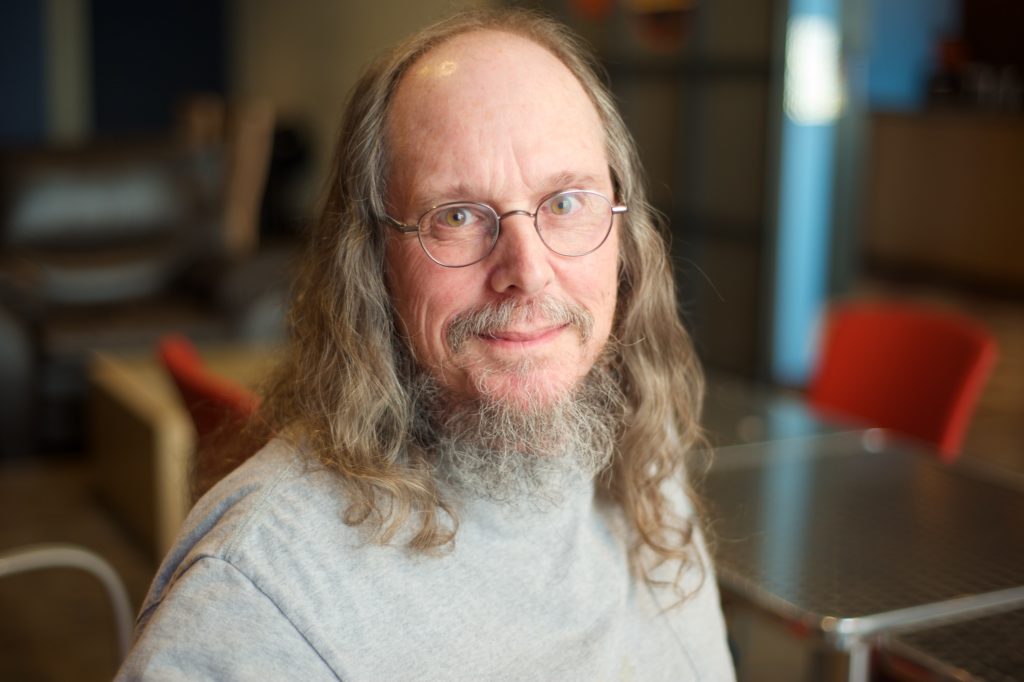

John Chasnoff: I’m co-chair of the Coalition Against Police Crimes and Repression (CAPCR) along with Jamala. I usually describe myself as an activist on police accountability issues. That seems to capture it to a large extent in a way that most people can hear it and it doesn’t shut the door too quickly. I used to think of myself as an organizer, but I don’t so much anymore. I tend to use the word activist because I don’t really think my strength is in organizing. I try to do a lot of the policy work for the movement around changing policing. And, lately, I’ve been trying to find more and better ways to communicate information both to the activist community and to the general public around what policing is right now, what some of the challenges are, and also to create the vision of how do we get to a world where we don’t need the police. That’s pretty far off in the future.

Jamala: 2039!

John: Yeah. That thinking might be a little quick. But, at least, what are the intermediate steps so that we can move closer to that and people can begin to imagine what that might be like?

How did you two first meet?

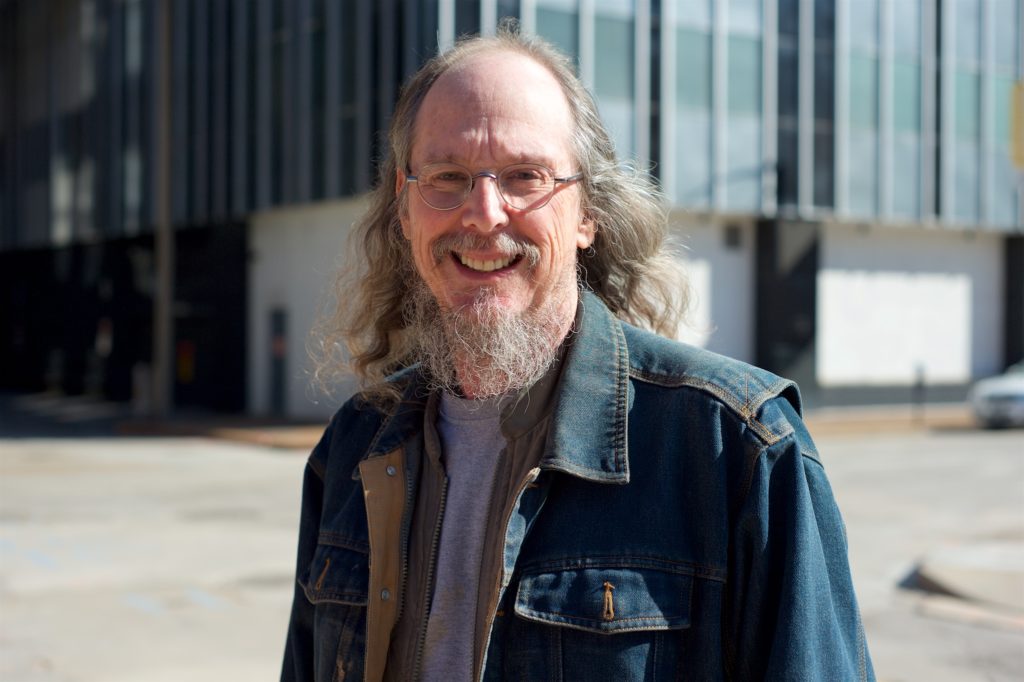

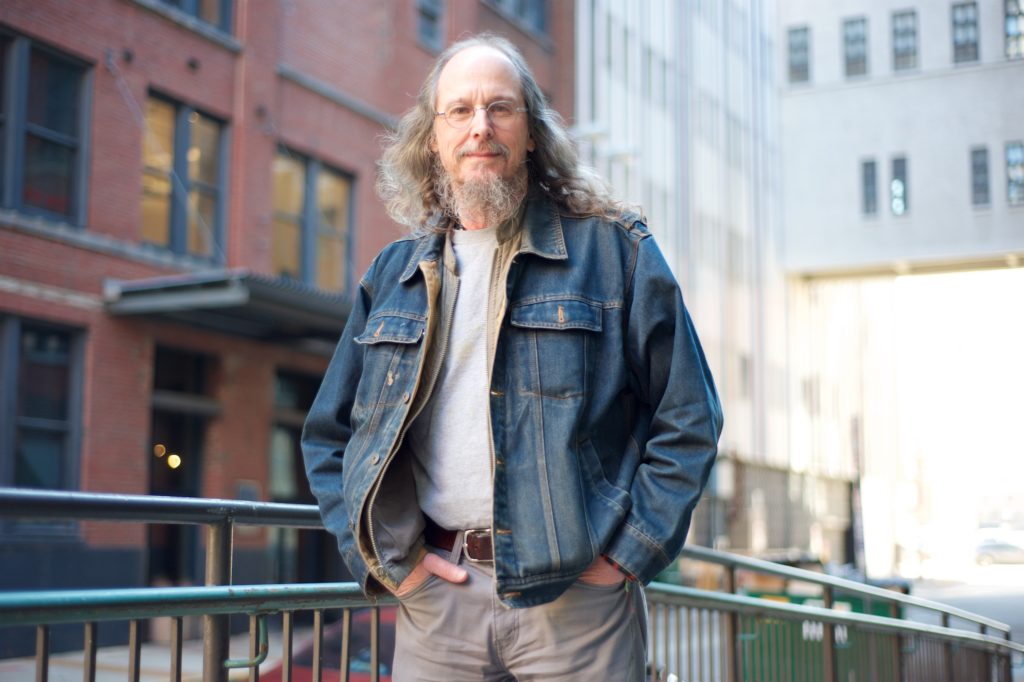

John Chasnoff and Jamala Rogers. (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis.)

John: I came to a meeting for the CAPCR. Just showed up.

Jamala: I’m glad you remember that.

John: I do. Because I was with a walker because I’d fallen off the roof. And you all were asking, “Did you get beaten up by the police?”

Jamala: It seems like we’ve been around for so long together that I had to remember when that first happened because quickly we saw his commitment and saw his interest. So at a certain point, he did sort of become our in-house policy person and then he became the co-chair. He and I do a lot of strategic thinking and scheming and planning together.

What have you learned about each other from working together so closely?

Jamala: He’s so committed to doing the work. If John says he’s going to do something, then I know he’s going to do it. So I don’t have to worry about that part. Sometimes we have differences in the tactical part of it, and then we both try to check each other when we get impatient about a particular process. I was just telling somebody, “We’re old. We’re not cranky yet. But we can get there quick with the foolishness that’s abounding around this town.” But, yeah, I can count on him to be honest and truthful to give me his opinion.

We’re old. We’re not cranky yet. But we can get there quick with the foolishness that’s abounding around this town.

John: There are three adjectives I’d use to describe Jamala. One of them is relentless. She mentioned 50 years. That’s a long-term commitment and she has been at this non-stop for all of those years and just keeps hitting at the issues. The other one I would use is fierce because she doesn’t truck with a lot of foolishness. She’s serious about revolutionary change, so she doesn’t want to waste her time or anybody else’s time. And the third adjective is principled. OBS has been known to be an organization that hasn’t backed down for all these years and what it stands for and how it does the work. The whole community looks to Jamala when they wonder what’s a direction to go that’s going to be a principled path to get us to a principled place.

What does it mean for your institution or others to be accountable to Racial Equity?

Jamala: In a place like St. Louis, one of the things I haven’t got weary of yet is the talk about Racial Equity. Now it’s a buzzword since Forward Through Ferguson. But what it means to people and how they are embracing it is different and sometimes not at all. We got the jargon. We got the talk down. But we don’t have the walk down. So part of what we have been trying to do, as it relates to police accountability, is to talk about accountability using a Racial Equity and racial justice lens. Because if you’re talking about the methods of policing and how they’re different from community to community, you can’t do the work without acknowledging that and trying to figure out how is that going to look different and how are we going to hold, not just police officials accountable, but other elected officials accountable. Police are accountable to a bigger circle of people. More than that, they’re accountable to the citizens. Sometimes citizens don’t understand their own power. And that’s another place we’ve been trying to cultivate and agitate and engage people – in the fact that whatever happens, you’re going to be a part of that. It doesn’t matter that you’re out there with a sign or you use a pen to write a letter. We’ve all got to be part of making the change.

It doesn’t matter that you’re out there with a sign or you use a pen to write a letter. We’ve all got to be part of making the change.

We have seen some of the narrative change. We have seen people get engaged and things happen. It was a 30-year struggle but, eventually, we did get local control of the St. Louis Police Department. And that was with naysayers all along the way saying, “It’ll never happen. Why you all think you can do this?” And now we’ve got local control, which means that the St. Louis Police Department is accountable to the citizens here and to the Board of Alders. Whereas, before, St. Louis and Kansas City were the only two cities in the whole country whose police departments were under the jurisdiction and authority of the governor. That dated back to civil war days. So our thinking was not that there was going to be some panacea, that things were going to miraculously change, that police brutality would melt away; but that, whatever the issues are, you were not going to have to appeal to the governor or go down to the State House three hours away to make your case. The case needs to be made at City Hall and needs to be made by citizens. And that, we thought, was very important.

It’s been a bit of a shift to get people to realize that you now have a locally controlled police department. I even had to remind our new mayor of that. “We didn’t fight all this time for you to give up your power to the police chief. You are where the buck stops. So you need to do what you’re supposed to do as the head of the city and the police department follows now under your authority.” During the Stockley verdict, we expected the mayor to say, “This is not going to be tolerated. Here’s how we’re trying to set the tone for this city.” And we didn’t see that kind of leadership coming forward. So it just made us ramp up our efforts around the selection of a police chief to show citizens need to be involved in this process. And they were. For the first time that I can remember, there was a citizen advisory group, there were forums across the city to ask, “What are you looking for in a police chief?” People may not be excited or satisfied with the end product, but the process was something that people hadn’t normally expected to happen.

We try to focus our work on the people who are most affected by policing and get the most disparate treatment.

John: In terms of Racial Equity, in terms of outcomes, we try to focus our work on the people who are most affected by policing and get the most disparate treatment, which is the Black community, primarily, and the lower class or working-class folks, secondarily. We try to make sure that whatever policies and changes that we’re pushing for, is that what folks from those categories want? Is that what’s going to be a primary help to them? And then there’s the internal process. The coalition has long believed in the principal of Black leadership. I had a lot of hesitation when Jamala asked me to serve as a co-chair here. I still consider her the senior partner in that relationship because Black leadership is really important. White allies tend to drift off track. They don’t always understand the issues or see it through the proper lens. Before every community meeting, we’ll try ahead of time to make sure that the crowd coming is representative of the community. And we hold ourselves accountable when we don’t live up to that standard. If you’re going to end up with work that’s focused on a community, then the way you get there is through a process that includes folks who are most affected in the whole process of the decision making.

Jamala: What tends to happen in this city is that there’s a lot of ‘rah, rah, rah!’ and then people go back to their corners, sometimes under rocks, and they say, “This too shall pass.” And then the next new thing is the new thing. So, Racial Equity is what we’ve been fighting for even before the term was popularized in the report. That’s absolutely at the core, and it’s across sectors and issues.

I do want to say a bit about the two of us being co-chairs because one of the things we said early on is that we did not want people to perceive police abuse as a Black issue only. If you do that, that issue gets marginalized, and then people who are non-Black think, “Oh, that’s their problem. I don’t need to get involved. Let them work it out.” In our organizing, we went across the city from north to south every time we had a mini-campaign. One of the campaigns was around local control. We had town halls everywhere. We did canvassing. And it was White people who actually took up some of that work. If people don’t see it as an issue, our responsibility as a civilized society is compromised and jeopardized. We don’t all see that even if we didn’t all create the problem, we should still be owning that problem, and then seeking to have some real humane solutions to it.

Sometimes people get stuck here for a lot of different reasons, but particularly around race. People want to maintain the status quo for lots of different reasons. Some of them who don’t even have status, try to maintain the status quo. So we try to get past those barriers and get people to own some of these processes. Some of that means trying to make it as presentable and accessible and, I won’t say, “Easy to get involved,” but trying to give everybody a piece of how they can move an agenda, move an issue. We’ve tried to do that and, in some ways, it’s been very successful. A couple of years ago, we launched a Re-Envisioning Public Safety campaign and said, “This issue is not just about more police.” The narrative at that point was, “For people to really feel safe, we need to hire more police.” And our thinking was, “There are a lot of police in our communities and we still don’t feel safe. In fact, more police is the problem.”

What would it be like if the 60 percent of the city budget that we spend on arrest and incarceration was redirected and spent somewhere else?

We started to get people to think about, what would it be like if the 60 percent of the city budget we spend on arrest and incarceration was redirected and spent somewhere else? We had seminars and town halls all over to say, “Dream of it.” We were actually surprised and encouraged by what people came up with, but they had to get out of that whole mindset that public safety’s only about police. It’s not. So we think we were successful enough that we changed the campaign to not just reenvisioning but reinvesting in public safety. That doesn’t mean police and the courts. It means some of the more human needs like jobs, recreation centers, and social services because a lot of those are at the root of crime and violence. And if people have issues – like, mental health issues or no job and therefore no money – lots of ugly things can happen as a result. So, police are the last resort. And that’s what we like to say. Police are the last resort.

Why do you keep doing this work after so long?

John: I can’t help myself sometimes. I wish I could back off a little bit, but I just can’t seem to stop. I don’t know if it comes from my upbringing. It’s hard to say. But, it’s difficult work. I mean, in some ways I describe it as throwing yourself against a brick wall over and over again. You get exhausted along the way. Any sensible person would stop. I guess I hold to some of the concern that it’s easier for me to stop as a White person. I can turn my back on the problem and walk away, and that prospect scares me. And what would that mean, personally, to do that? So I keep going.

I can turn my back on the problem and walk away, and that prospect scares me. And what would that mean, personally, to do that? So I keep going.

Jamala: I was told many years ago by an elder, “This is a long haul. It’s not going to happen soon. You’ve got to be a marathon runner instead of a sprinter.” So you adjust your mindset as well as your body to facilitate that. I would say we’re in pretty good shape. We’re not popping pills for this, that, and the other. But it is a realistic vision of what you can do. As long as you’re moving, then that’s enough ground for you to be re-inspired to continue.

And if you surround yourself with people who share a common vision and the same values, then it’s easy to stay focused and centered. Otherwise, you get frustrated or demoralized because it looks like nobody understands or nobody’s doing anything. You just need to pull yourself out of that setting and get to another setting where people are in motion doing critical thinking about what’s going on and putting together action plans. That’s where people get stymied, like, “I see this big problem. I don’t know what to do. I don’t even know where to start.” So we try to get people some tools:“Here’s what you need. Here are entrees into the problem. Pick whichever one you want to start working on it.”

John: I had a spiritual teacher who used to say:“It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon.” I started saying:“It’s not a marathon, it’s a relay race.” That 2039 seems almost too close because we’re going to have to pass the baton several more times. So, yes, it does really help to keep that timeframe and perspective and not expect it’s going to change tomorrow. Have a plan for being able to move it this far forward and then try to reach that goal. You have to keep your eye out there on the long-term vision because you’ve got to make sure you’re moving towards that.

I had a teacher who used to say:“It’s not a sprint, it’s a marathon.” I started saying:“It’s not a marathon, it’s a relay race.”

The Re-Evisioning Public Safety campaign is a big part of our work right now. We’ve also put together a presentation that we’re going to release to the public about transforming police culture because part of the work has to be changing the mindset of policing from the individual officers to the culture inside the department, the mission, what the department sees itself as doing. We’re involved in Ferguson on a consent decree process because the words they put on paper are very transformative, but how that gets translated into practical, long-term impact in Ferguson will have a big impact on the region as a whole. So we’re concerned with trying to make sure that the vision captured in the consent decree is actually being implemented.

We’re also working on policing surveillance issues. St. Louis City is building a surveillance hub in the city now which has a huge impact on people of color and on civil liberties. The coalition is working to stop it if we can. Or, at a minimum, get some decent civil liberties policies in place. The surveillance hub will be housed in the St. Louis Police headquarters and it’s a technological center that brings together street cameras, license plate meters, ShotSpotter, and some of the more old-fashioned intelligence-gathering networks all into one place so that the information can be synthesized and used for whatever purpose. Supposedly, it’s for crime fighting, but we’re concerned that it’s being used for other more repressive things as well. One of the historic jobs of the police department is to suppress people of color. One of the roots of American policing is in slave-catching patrols. From our very beginning, the police were set up as a repressive institution to keep certain parts of our population under control. There’s been a lot of talk about the new Jim Crow. We had slavery, then we had Jim Crow, and now mass incarceration. All being methods of suppression. To our way of thinking, surveillance is one of the major components of what comes after mass incarceration to control the population.

Jamala: We’ve seen a lot of anti-protest bills introduced on the state and national levels. So even people who want to exercise their constitutional right to assemble, those bills are going to make it more difficult for people to participate in that way. So the repression arm is stolen away from this whole crime-fighting piece that folks have bought into:“Of course I want a camera on my block. I want to be able to…” We have to tell people in the Black community, “Listen, that’s not for you. Those are for business people that are in the Central West End and Washington St. downtown.” And, also, if you’re still complaining about shots fired and crime on your block, what good has the camera been doing for you? It comes at a cost, in terms of the purchase and the maintenance. So we’ve been trying to do some more education around that, like, “Investing money in cameras is not going to get you that feel good, safe feeling. That’s what you’re yearning for, but that’s not going to do it.”

John: Well, one of our big projects was to get a Civilian Oversight Board (COB) for the City of St. Louis, and that campaign started in the early 80s. But the second round of that fight started in about 1999 or 2000. We started a serious push to get civilian oversight and we were able to achieve that in 2015. That was a long struggle there. But what happens in a lot of cities is that they’d get a civilian oversight, they’d break out the champagne and have a party, and then everybody would go home and think, “We did that! It’s done.” But we have been committed to following up with the COB because there has been a very interesting process of implementation of that board and ongoing oversight of the oversight board that’s necessary to make sure they’re really doing their job, that they have the powers they need, that they’re using the powers they have, and they need a push along the way to keep on that. Who knows when the work around civilian oversight will stop. It definitely didn’t stop when we got the board.

We’re probably the last urban city in the country that had a Civilian Oversight Board.

Jamala: One thing that was interesting for us is that we’re probably the last urban city in the country that had a COB. So when we began to look at our legislative model, we looked all over to see which models worked and didn’t. We were able to take the best parts out of all the models, and what we came up with, is if all the members are appointed, that’s not going to be good. If there’s a line item in the budget – if there’s a non-funded mandate – that’s not going to be good. So when we went into the legislative fight, there were things we couldn’t compromise on because we already knew the ending to that story and we didn’t want it to happen here.

John Chasnoff and Jamala Rogers. (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis.)

What John is talking about is that this is an experiment for us. Even though we took the best of all of those pieces, we still don’t know, how is this going to work here? The first iteration of board members is struggling to find their way, so we want to give them space to learn and grow. But we also want to be there to say, “Whoa, you need to be doing this…” One of the things we’re clear about is that they need to open up the process to the public. You can come to the board meeting and hear them make a recommendation about a particular case, but you have no idea about the particulars of that case. I don’t think we’ve asked for names and addresses of people, but we do need to know a little bit more than a number. So we’ve gotten them to move on that.

The other thing is having the COB move around so people know that they are an entity. As best as we publicized that, there are still people that don’t know there is an independent entity that can take a complaint from a citizen and they don’t have to go to the Internal Affairs Division. That’s still unknown. If this body is going to let people know that they are there for the community, then they need to be at more community meetings and getting out and talking about how this board works and how to access it.

The boards that were able to look into police policy and make policy recommendations were sometimes more able to change police culture.

John: It was really important to us too that we gave the COB two primary functions. One of them is the one that gets all the attention, which is to review and make recommendations around complaints. But Jamala was talking about best practices around the country, and we saw that the boards that were able to look into police policy and make policy recommendations were sometimes more able to change police culture than the ones that just looked at individual officers and complaints. So we gave that second power of reviewing and recommending changes to policy to our oversight board. That’s a function that they have barely scratched the surface on so far in their first year and a half. We have been pushing them to do more of that work and not get so caught up in the complaints thinking they’re doing their job when there’s this whole second half of the mission that is crucial to address.

With all the work you’re doing, what’s the biggest obstacle in your way right now?

John: If I had to pick one, I’d pick the deference that our society gives to police. That permeates so much of our work. If an officer is on the stand, officers lie on the stand. And if you talk to defense attorneys, they know it. But the juries will tend to give deference to the police officer’s testimony over somebody else’s. And we see it all the time with the narrative that police are there to serve and protect and that there are heroes. That narrative is built into the culture that it’s almost like the first big hurdle we have to get past before we can get into serious, realistic work about what’s actually going on.

Jamala: I would say the biggest need is the additional people who could do the work full time. Most of the coalition, particularly the steering committee, are all volunteers who have jobs and families. We don’t have a huge budget. We have operated on sheer commitment and passing the hat around. So if we had folks who could actually do what we visualized, that would help. For example, we came out of the legislation with a district map and the district map is how we get the members for the COB. There are seven districts based on four contiguous wards. What we’d hoped to do is to create what we call district organizing circles in each one of those wards for people to, first of all, help neighbors and other residents to understand that they have a COB now.

Folks have to know that you’re there and you’re working on their behalf.

And also to help us keep the board accountable and help give them information and support. It’s not just about every time they do something wrong we’re gonna have a prod for you. And when people start attacking, we’re going to be the ones that support you. But folks have to know that you’re there and you’re working on their behalf. So we haven’t been able to get that off the ground like we would like to. We have organizing committees, and we might get somebody who says they’re interested in being a part of it, but then something happens in their life, and they have to fall back within the whole district organizing circle. So if we had somebody who’s main thing was making sure that these district organizing circles were not just created, but supported and sustained, I think we’d see a different kind of accountability for the police. But also for the citizens and that they feel like they are a part of an entity that has been out of their reach for a very long time, and whose salaries are absolutely being supported by their tax dollars.

Police are supposed to be working for us, and, really, is that the case even when they’re called? In most Black communities, they will say, “I called the police and nothing happened. I waited for hours.” Why would you want more of that? We have to do something else around the way policing looks in our communities and people are trying to figure that out. We had a community meeting called Community Policing:What it is, What It Ain’t. There’s such a broad range of views about what community policing is. Is it a police riding on his bicycle and talking to you and passing out candy to the kids? Is that your idea? Or is it when police are actually being stakeholders in that community?

How are we going to have a uniform approach to policing and what happens when those officers don’t do that?

We think we fleshed out what we think it is. But then there are communities that think police don’t need to be in their communities. They have lots of suspicion about police when they’re in our community. Because where we are, most of the time, they’re up to no good. So even though we have a view of policing on the outside, we also want a view of police officers themselves and about what it means to be the police. So when they get to the academy, we have to be assured that they’re not getting Training Day training, like the movie. We’re talking about how are we going to have a uniform approach to policing and what happens when those officers don’t do that. What happens when they violate their own code of ethics or their own policies? Why are there no consequences when we know people have done wrong and we can’t ever get an answer for that?

There have been clear violations and sometimes even the Black police officers’ association pointed out incorrect things and it’s like, “Well, so what? That’s the way we do it.” They don’t say that, but it’s almost like, “Well, this is the way we’ve been doing it, so we’ll continue to do it.” So we have to have a mindset that we have an idea of how police are supposed to be operating in our community. And when they don’t do that, we want to hear from you. Everybody doesn’t have to be fired. The punishment’s got to fit the violation. But, still, no matter what they do, nothing happens? Nothing?

The punishment’s got to fit the violation. But, still, no matter what they do, nothing happens? Nothing?

John: There are two things Jamala said that I’d like to pick up on. One is that the progression of what happened with the phrase community policing is kind of a proper warning for folks who are now working on Racial Equity because community policing is a term that got widely adopted in the 80s and the 90s and you can hardly find a police department that won’t say they do community policing. But along the way, it got watered down to the point where it’s become almost meaningless. We’re trying to restore some real meaning to community policing. So sometimes when I hear the phrase Racial Equity being so widely used in the community, I think a group like Forward Through Ferguson has to hold a standard. Even if it results in that word being used less, it needs to be used properly.

The second point is about how Jamala talked about our need for people power to get this work done. It’s been a very interesting process to watch. The Ferguson uprising was a huge infusion of energy into the movement around policing in St. Louis. So we have a whole lot of people who are energized and involved, but it’s surprisingly difficult to translate that into work, or at least the kind of work that we do. There are folks who just want to protest and there’s a definite place for them. We need protesters. We need folks to put their energy there. But the work can’t stop just at protesting. That tends to be unsustainable for a long period of time and it doesn’t necessarily point in the direction of the changes that need to happen. We need folks who are willing to do the other kinds of work as well and for various ideological reasons, some people just want to overthrow the police and they don’t believe in the step-by-step process to make that happen. Or they want to work individually, and they don’t believe in organizing. There are a lot of obstacles to overcome and discussions to have with people who are energized about this. So where do they put their energy next? And that’s a process we’re still going through three years later.

How could a Racial Equity Fund in St. Louis benefit the work that you do?

Jamala: It depends on what it’s set up for. If I knew that, I could say, “We’re doing this part of it that speaks to the recommendations of the report, and can we get funding for that?” But I don’t really know what it’s for, who the administrators are, and what you have to do to get it.

John: The Ferguson Commission did a great job and came up with really good calls to action. But at the time, I wrote a piece called Ferguson Commission:Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full? I thought there was a lot missing and some of the reforms got watered down or slightly misplaced. And even if they hit the mark, things change. New ideas evolve. For instance, the Ferguson Commission recommended that there be independent investigations of the police and that it goes to, I forget if it was the Attorney General or the Missouri Highway Patrol. In either case, that’s not where we would like to see it end up and there’s been some further thinking since 2015. So a Racial Equity Fund has to work with the spirit of the calls to action.

A Racial Equity Fund has to work with the spirit of the calls to action.

Circuit Attorney, Kim Gardener, and her office have said that they would like to take over the investigations of police shootings rather than send it to somebody at the state level. First of all, the Attorney General was elected by the whole state, which is a very conservative state, and he’s not necessarily looking at these issues with the eyes that we’d like to see. And it makes more sense in principle to keep the investigations local where whoever is doing investigations is more in tune with the thoughts and feelings and outcomes that the local populace wants. So Kim Gardener’s arguing to keep that in her office. We’ve advocated for a new city department which would be called something like a Department of Civilian Oversight, which would house the COB and the investigations of officer shootings. Even the prosecutor works very closely with the police and sometimes has conflicts of interest in terms of her ongoing work versus holding police accountable. So we’d like to see a civilian body doing that. It’s very much in the spirit of what the Ferguson Commission was talking about, but different.

People are paying attention to what we’re doing in the city, especially when folks said that it couldn’t ever be done.

Jamala: When you read the calls to action and you know that something is probably going to happen and then you try to get in front of it, we think that’s what the police department did when they set up the Force Investigation Unit to investigate police shootings. They put two people in charge of it that were very inappropriate with all kinds of character issues. So those people had been removed. But, again, what is the thinking? If you want to have a Force Investigation Unit, wouldn’t it be in your best interest – and this is just common sense speaking, not even Jamala speaking – don’t you want to have somebody there that’s got some credibility in which you can’t point out a pattern of abuse that they have? I mean, those are really the two people that you think are going to be in charge of investigating other police who have been charged with wrongdoing? It’s like a joke. And they were all White. Really?! C’mon y’all. Racial Equity. Let’s have a discussion about the people who could help us think this through.

C’mon y’all. Racial Equity. Let’s have a discussion about the people who could help us think this through.

We know from past experiences with prosecutors that if they don’t do what the police association thinks they need to be doing, then they tell their folks not to cooperate and participate. Sometimes you need that participation and cooperation to prosecute a valid case. But if they’re going to stand down out of retaliation, then you really can’t do your job. So we think that moving that to a more neutral area will probably be better for both parties.

One thing is the whole issue of communications and marketing around police and how people can get involved and the whole notion of the district organizer circles. But also to get people to better understand the COB and the legislation is supposed to talk about this. it’s in their interest to go out into different communities and say, “Hey, I’m Joe Blow. I’m on the COB and I want to explain to you what this does and what your relationship is to it. Feel free to ask me any questions.” That’s not happening. So if we could maybe get some brochures, maybe do some PSAs on TV and the radio. Some of them are free, but sometimes you’ve got to pay big bucks for those things. We need a whole campaign to just deal with that.

John: It’s an expense for us that’s hard to cover sometimes. We could use a full-time staff person. That would up our ability to function tremendously. And, here’s a great example. So the COB was having trouble getting people to file complaints during the Stockley protests. So we said, “Well, rather than sit in your office and hope complaints come your way, why don’t we have an event where you make yourself more available? We’ll have pizza and have an afternoon specifically designed and publicized.” They said, “That’s a great idea. We don’t have any money for pizza.” So we had to come up with the pizza. We end up digging in our pocket sometimes to make something like that happen. So funding could be a huge benefit on a bunch of different levels.

Jamala: And it’s not that we couldn’t find someone to donate the pizza, but even that takes time to call around and let people know this is what we’re trying to do.

John: One of the threads of our work for all these years has been as a first responder to families whose family members have been victimized by the police. We work then with that family over the long haul to try to get justice and we have been wondering about who else might be able to help do that kind of work. We’ve put together a presentation on what it means to respond to a family and how different groups might be interested in doing that kind of work. We put together a brochure, too. So that’s got to get printed, and it was volunteer time to put the brochure together. And we have a website, but you also then need to then go to the event where you’re pitching the idea and hand out the physical brochure.

Jamala: Speaking of websites, we need somebody to help update that. We just don’t have the time.

John: I would like to just say this. A lot of our work is focused on the St. Louis City Police Department and we have something like 57 police departments in the region. And especially with the county police, there’s a huge gap in terms of the work that needs to be done. We work with the city police department for a variety of reasons, but sometimes the county police department is a harder nut to crack. And one of the reasons why we don’t get out there is that it is such a hard nut to crack. Besides needing to increase the efforts for what we’re currently doing, there is a huge regional problem that’s barely getting addressed. And that is how to bring civilian oversight to the county when you have all these various small departments? We came up with a strategy for that, but haven’t had the manpower to push that and make it a campaign and try to get that in place.

Jamala: The other part of it is because we don’t have the capacity to go region-wide, our focus has to be in making this model work so that it can be replicated. So if you do the job right and say, “Oh, this is what they’re doing and how they got it to happen…” Because we haven’t been able to make inroads into the county, people are paying attention to what we’re doing in the city, especially when folks said that it couldn’t ever be done. You shouldn’t tell determined, fierce, relentless activists that they can’t do something.

What’s your vision for St. Louis in 2039?

John: One of the things that I think is doable by 2039 is the vision that we’re trying to put forward in Re-Envisioning Public Safety. We tend to think of public safety as crime. And we tend to think of crime as police. We need to break that train of thought. People are not safe. It’s a public safety issue when there’s not enough affordable housing. It’s a public safety issue when there’s not adequate healthcare. And those things vitally affect crime. How do we get to the root causes of crime and solve it on that level instead of reacting to crime and creating a mass incarceration problem? And I do think that by 2039 we could get to a place where we have rehabilitated our resources in a way that doesn’t just react, that doesn’t just punish, but gets at the root causes and solves some of these chronic endemic social issues that are really the drivers of a lot of public safety problems.

Jamala: That’s absolutely correct. The whole notion of policing has to change. The culture definitely has to change. But, like poverty, crime has been racialized. So when I think about the crime that actually compromises and jeopardizes public safety, I think about some of the policies coming out of the Trump administration that are going to impact the quality of people’s lives. So it’s not just somebody snatching a pocketbook. It’s the bigger picture of policy and legislative issues that are now being overturned. And those definitely impact people’s public safety.

The vision of a broader understanding of public safety is what would definitely change with the Racial Equity lens. I’ll be 89 by then, so I don’t know if I’ll be of sound mind and body, but that’s what I would be looking for. Has that view of policing changed? Has that view of public safety changed? Has that view of who’s committed crime changed? And what is crime? White-collar crime is far more devastating to large swaths of people than holding up somebody to get their iPhone. I’m equally concerned, if not more, that those big-picture policies are impacting our quality of life and that trickles down to the way people respond and react to one another.

John: An ex-professor from Webster University had just stolen $375,000 and she got probation to write in a journal about why she would have done such a thing. No prison time. Somebody who steals $50 on the street is going up the river. So we tend to think that the police department is this indelible institution. We can’t see our way past it or around it. And, historically, we haven’t always had modern-day policing. It came about during the industrial revolution and urbanization, and as an institution, it’s less than 200 years old. We have to remember that when we think about change. We’re moving into a very different society than what was created by the industrial revolution. So it’s not beyond imagination to think that we can rethink public safety and policing. I don’t know if it will be out from under industrial revolution policies by 2039, but I’m hoping that we’re moving in that direction by then.

John Chasnoff

Co-Chair, Coalition Against Police Crimes and Repression

Jamala Rogers

Executive Director, Organization for Black Struggle Organizer, and Co-Chair, Coalition Against Police Crimes and Repression

#FwdThruFerguson