This is part of the #STL2039 Action Plan storytelling series in partnership with Humans of St. Louis.

Jackie Hutchinson: I am the Board President of Consumers Council of Missouri. CCM’s mission is to educate and advocate for the collective interests of consumers through leadership and partnerships on issues such as utility rates, personal finance, health care access, and others as they arise. I am also co-chair the St. Louis Equal Housing and Community Reinvestment Alliance (SLEHCRA) along with Elisabeth. The work we do brings about Racial Equity and equity in low-income families and communities. In terms of housing and banking access to loans, we help bring equal access to people who really don’t have that.

Elisabeth Risch: And I’m an assistant director of the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council (EHOC), a fair housing organization. I’m also the co-chair, with Jackie, of our SLEHCRA Coalition. I see my role in both of these entities as an advocate, a researcher, and a coalition builder. A lot that we’ve done with SLEHCRA, really the power we built as that organization, is through the coalition and bringing together different leaders and organizations concerned about access to investments. We’ve been able to mobilize that into real changes as it relates to access to financial services, access to housing, and community reinvestment. SLEHCRA has been around for eight or nine years. We were both there from the beginning. I started out not knowing anything about fair housing or about the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Through building coalition and making connections, we’ve figured out how to do this work.

What does it mean for your organizations to be accountable to Racial Equity?

Jackie: The calls to action that SLEHCRA is working on are to bring about equity in banking and lending, which would lead to equity in homeownership, equity in wealth building, equity in choosing where you live, and in being able to access the resources that you need to stay. Just providing equal access that does not exist in the St. Louis area is huge.

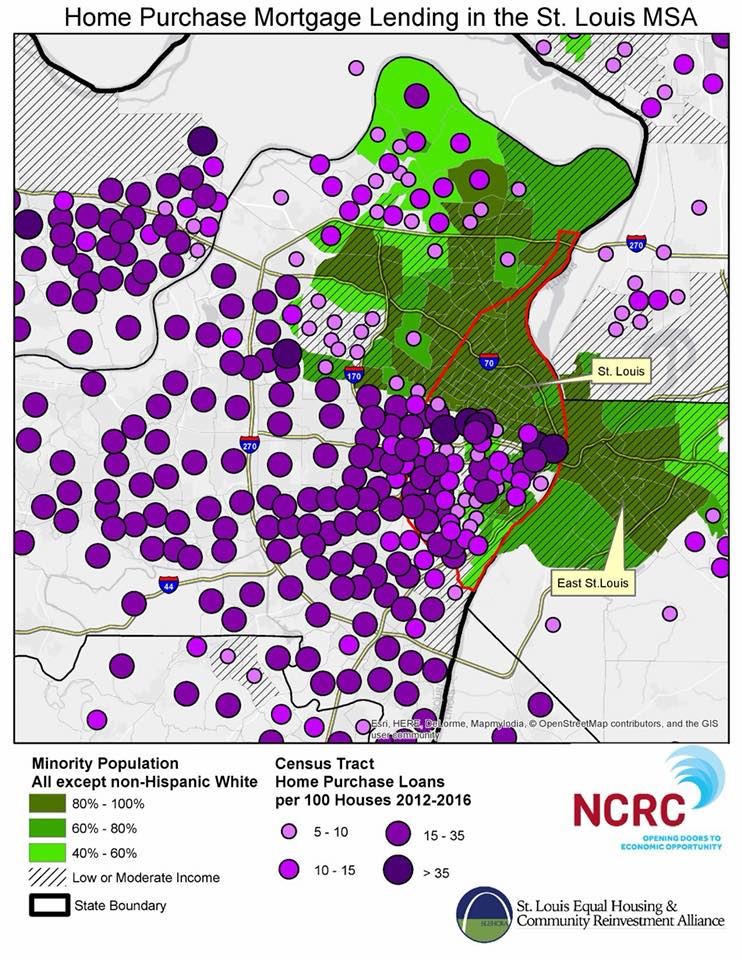

Elisabeth: The specific calls to action for SLEHCRA are around opportunity to thrive and access to financial services, asset building, and housing and are all related, as well as making sure that the CRA is strengthened. The action stuff is addressing specific racial disparities in financial services because there are a lot of disparities around low and moderate-income individuals. There’s still discrimination in housing, banking, and mortgage lending depending on the color of people’s skin and the color of the neighborhood.

You both didn’t really know about this type of work before you started. Now, you are the ones to go to for all this information and the ones advocating.

Jacqueline Hutchinson (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Jackie: We had to learn quickly. One of my staff said, “I went to a meeting, and this coalition is forming, and you have to be at the table.” Then the next day she said, “Did you call?” She was really pushing me, so I picked up the pamphlet and read it and I realized, “I do have to be a part of this.” I got more information and got permission to join the group. I had done a lot of advocacy in other areas, but not in CRA, or housing and justice, or any of the areas that I was stepping into. The platforms experience I had, however, prepared me to move seamlessly from the work I was doing. So to add this on wasn’t a stretch. I was aware of housing discrimination, I just wasn’t aware of how the CRA impacted it. I was aware that there weren’t banks in lower-income communities, but there were more payday loan stores and folks couldn’t get home repair loans. Just from having an office on Martin Luther King Dr. for 15 years and providing social services, I knew what the problems were. I just didn’t know where the solutions would come from and that we needed to be working in that area.

Elisabeth Risch and Jacqueline Hutchinson (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Elisabeth: Yeah, so in 2009, EHOC and some other organizations, like Justine Petersen and Missourians Organizing for Reform and Empowerment (MORE), had been addressing foreclosure and lending issues. As a fair housing organization, we were seeing a lot of problems with weird loans coming through in which people didn’t know what type of mortgage loan they had gotten. So the group of organizations started this coalition called SLEHCRA to address the financial services issues. We were learning about the CRA from one of our national partners, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRA).

We really had no idea what we were doing. So that’s when I joined and realized I was good at doing data analysis and looking up mortgage lending data. I would figure out how to look up when banks were scheduled for exams, to see how they were meeting the needs of the community. We started doing our own evaluations of how banks were doing, how they were serving the needs of low- and moderate-income communities and communities of color. Then we started writing these comment letters to banks and to the banking regulators saying that we have some concerns because we saw that banks were not providing equal levels of access to low-income communities. We had concerns of how they were serving the needs of African American borrowers. Actually, this bank here was one of our first cases.

So we did a data analysis of their performance and found that they had not originated a single loan to an African American borrower in St. Louis for five years. They had branch locations in West County and South City. Then we looked at their assessment area, where they say they’re providing services. This is before I’d gotten super technical with GIS stuff, but I laid out a map of all the census tracts and highlighted that they had excluded parts of North City. Essentially, it drew a line down the middle of St. Louis. If you know anything about St. Louis, you know that if you draw that line, there are clear racial disparities about who you’re including and who you’re excluding. We were seeing those trends with individual banks and, in this case, we didn’t know what to do with this bank that clearly looked to be discriminating. NCRC helped us guide the way, and we filed some fair housing complaints and enforcement actions with the Department of Justice.

Jackie: When we started out, we tried to meet with them and the meetings didn’t go so well.

Elisabeth: Some of them choose not to meet with us.

Jackie: They must have wondered, “Who are those people to demand a meeting with me?” We did give them the opportunity to sit down with us and try to come up with some solutions that would help right some of the wrongs. We were offering to help, not just demanding that they do something, but saying, “Here’s a collaborative that wants to help you do this.” They didn’t want to meet with us at all. So from there, we filed the fair housing complaint.

Jacqueline Hutchinson and Elisabeth Risch (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Elisabeth: What our work now symbolizes is that we’re using what organizing and policy we have available to us in order to help change practices of other institutions that have real obligations. There are laws that they have to comply with and, even if they don’t, there are penalties. So we act like accountability checks for all of those laws. Also, we’re helping to form partnerships and relationships to change the cultures of how banks typically operate. For example, we make sure that they have a branch, like this one, that’s located in a predominantly African American community, and that has people who work here look like the people that live in the neighborhood, and that there are products that better serve the needs of all communities. Regardless of people’s income and race, banks have this obligation to do it and they just need to do it. Midwest BankCentre is actually a really good example of a bank that has gone from one end of the continuum to the other. Now this bank is one of the leaders in lending to African American borrowers. They embraced this as a line of business and have seen that they’ve been able to make money from it. An important angle that we’ve tried to hone in on is: It’s not just because you have to do it. It’s good business. It will help your bank. Otherwise, you’re missing out on all these opportunities.

Jackie: Right. This is their second bank in a low- to moderate-income neighborhood. The first one was in Pagedale. Within two years, that bank had the profitability they were projecting to make in five years. So they realized if they partnered with the community, with businesses, with other nonprofits – with people and organizations that were already trusted in the community – that customers would come to their bank. They did so well there that we said, “We need a bank on Martin Luther King Dr.” and suggested some organizations they could partner with.

So, we meet regularly with banks and some of them welcome our suggestions now. They ask us, “What can we do better?” We asked to offer home repair loans, for example, since many didn’t have them or they weren’t accessible to low- and moderate-income people, and certainly not in neighborhoods that were African American where they were actually letting them know. Some banks may have offered this type of loan, but nobody knew they had the loan or that people could get the loan. So when they’d say, “Well, we’ve got this loan, but nobody applies for it,” I’d say, “I wonder why that is, because there’s plenty of people who need home repairs. There are plenty of folks whose roofs need to be replaced and need new windows. Yet, they don’t think they can get a bank loan and don’t feel welcomed enough to walk into your bank and ask.” So we’re changing all of that with our collaborations and partnerships. It’s a slow change, but with the right partners, banks are making inroads.

Jackie: And like Elisabeth said, we have two different skill sets that are necessary to move this collaborative forward. I could not have done this had it not been for Elisabeth making the data understandable. Even with a master’s degree in policy analysis, I don’t have the time to learn all about the CRA, or interpret all the reports, or any of that stuff. Elisabeth is brilliant at summarizing the data, telling us what we need to know, pointing out what it means, and allowing us to move forward with a clear understanding so we can base our action on clear facts.

Jacqueline Hutchinson (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

We meet with banks and they tell us how hard they’re trying – and they really are trying hard – but, “The data says you only made two loans to African Americans. There’s still a disconnect.” We can stick to the facts, we can say, “Yeah, you donated to the Girls & Boys Club. You did some great things. But the issue is did you provide any loans to African Americans or other people of color? If not, what are you going to do to fix that? How can we help you fix that?”

Elisabeth: And Jackie is a huge asset and leader because we wouldn’t have gotten to the place we are in our coalition if we didn’t have leaders able to give real, concrete solutions and throw out ideas. Like, “Here’s what our community needs. There are home improvement loans and here’s how they need to be set up. Here’s what credit score requirements you should consider or perhaps not consider any credit requirements because here’s why.” What’s brought a ton of value is the ability to point out those solutions and develop the action plan, too. A lot of the partnerships that have come out of this are from Jackie coming up with the ideas, connecting them to what’s going to make them happen, and then her saying, “Go meet with this organization.” Or, “Here is where all the people are. Go there.”

Elisabeth Risch and Jacqueline Hutchinson (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Jackie: Elisabeth and I can ask tough questions without being insulting. It’s not just us that have to endure it, it’s the whole team we work with. But, we can sit in a meeting with people who do everything but call us bad names and not respond to that. We met with one bank, Elisabeth would ask a question, and the banker would address the men in the room. I would ask a question and he would do the same. He wouldn’t even make eye contact with the two of us. We just kept shooting our questions. We never personalize it because once you personalize it then you get off track. It takes you off the issues and gets you off balance. So we stick to the facts even if people are telling us all the wonderful things that they do: “We give money to the senior citizens, and we take little kids to camp, and we do all these wonderful things that are really necessary.” We listen and we say, “That’s great. Get back to what the data shows.”

Elisabeth: Jackie’s good at asking important questions at the right time that they don’t want you to ask, like, “What do your loan officers look like? Do you have any people of color on staff?”

Jackie: Yeah, because often the banks want to talk about the good stuff that they’re doing and their staff who serve on their boards, but all of those things are not putting branches in neighborhoods where they’re needed. Don’t get me wrong, we don’t minimize the fact that they’re doing the good things that they’re doing. But what we’re talking about is Racial Equity and equity for low-income neighborhoods. “If that’s not part of what you’re doing, you’ve got a lot of work to do.” So, yeah, we work really well together in making sure that we’re respectful to the banks, but that they know we’re serious and we can’t be thrown off track. If they’re trying really hard, but they still didn’t loan any money to Black people, that’s not good enough.

You’re holding people accountable and you’re a White woman and a Black woman doing this work together as a team. Can you speak a little more to that?

Elisabeth: Our coalition is made up of about 24 different organizations. We have a steering committee of about 10 people. Most of the steering committee leaders and the people who just show up are women, and mostly African American women, which is a really powerful dynamic. We all walk into a bank boardroom and sit down and ask these hard questions. No one there really expects that.

Jackie: I think it makes a very powerful to have the two of us leading this coalition given the fact that the majority of bank executives are older White men. But our strength lies in the commitment of our steering committee leaders who come to the table with us, ready to negotiate for the benefit of the community. The diversity of the representation in the group allows us to make sure we consider all underserved and marginalized segments of our populations and allows us to address varied topics as a group.

Elisabeth Risch (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

How have you built Racial Equity into your institutional DNA?

Elisabeth: It’s hard to answer because my organization is a civil rights organization and I’ve always been fighting discrimination on the basis of race. Obviously, I’m White, and grew up White, and have White privilege. So, for me, it’s realizing that it’s really important to be investigating these things and to be pointing it out in the data. It’s also recognizing that I’m sitting at my computer looking at the data from a different perspective than someone who experiences this when they walk into a bank or to meet with a real estate agent or landlord.

It’s been powerful for me to experience this at an organization that cares about this and is mostly led by people of color. Part of what shifted was making sure that we’re being explicit about that Racial Equity lens, not just in the work that we’re doing enforcing laws outside, but within the organization, too. What happened in Ferguson has made for more intentional discussions about who’s making the decisions around our table. Who’s speaking at our table? How are we thinking about these dynamics, not just within the banks, but with the lenders and housing providers? Sometimes that means setting aside some of my schedule and keeping other appointments or making sure that I’m not the only one talking or leading a meeting when there are people that are much better equipped and have much more powerful testimonies to share than I do.

Jackie: Racial Equity and equity for low and moderate-income communities is built into our institutional DNA through our member organizations. Most of our member organizations have long histories of fighting for the rights of marginalized individuals and communities, fighting poverty, and striving for economic justice. The rich histories of the organizations who choose to do the work and the passion of the members around the table keep us grounded as an organization.

Can we talk a little bit about the Racial Equity Fund? Has your organization invested in it? Do you know what it is?

Elisabeth: I just know that it’s in development. My idea is very limited about what it could do or help fund.

With what you do, why do you think it’s important to have a Racial Equity Fund in St. Louis?

Elisabeth: From seeing the lack of investment in certain places in St. Louis, or specifically how banks or other community development projects are investing, that oftentimes those are because of the law like the CRA or other forces and the pressures are encouraging people to invest in those and those don’t necessarily have a Racial Equity focus. The CRA is a race-neutral law. There’s no kind of explicit racial component to it at this point. Something that we’ve seen from the newest report from Reveal and the Center of Investigative Reporting looks into is how sometimes banks and other community development investors will exploit the CRA to cause gentrification. So, if you’re looking at what neighborhoods are getting reinvestment dollars in St. Louis, it’s often focused on how are we bringing more White people to these neighborhoods and there are a lot of unintended consequences that happen in which residents that have lived in a place for years are getting pushed out. So, I see a benefit to that Racial Equity Fund focusing on a really explicitly racial component that addresses some of those issues of how are we rebuilding communities, not just with new residents but with existing residents? How are we helping to build their power?

Jackie: I’m not really that familiar with it either, but I would hope that part of what the Racial Equity Fund would do is fund projects like SLEHCRA. That would be wonderful. There’s not a pot of money to do advocacy work. We could have so many more supporters and educate people about what CRA is and what their rights are and what is available to them even as a source of funding that could be utilized to help increase the capacity of the folks doing the work. We’ve built into our community benefit agreements some money that supports the work that we’re doing, but we really don’t have a source of funding. We figure it out as we go. Wouldn’t it be great if there was some organization where part of their mission was to make sure that people like us and plenty of others in the community that really want to be doing this work, but can’t figure out how to fund projects, will bring about some Racial Equity? Or bring together groups of people who could talk about it?

Elisabeth: What a fund could help us do would not just provide capacity to run our organization, but there’s a big need for organizing capacity in St. Louis. There are a lot of service-oriented organizations that are very transactional and there’s a lack of focus and resources on how to organize and build power. So it’s not just a continuing, transactional, helping people kind of address their emergency needs, but how are we then building us all up further to address some of the larger systemic issues? I don’t think that there’s any kind of funding for not just the advocacy, but the organizing.

Also, there are so many good innovative ideas about how to address multiple abuse calls to actions. Like, how are we increasing asset building and access to homeownership? There aren’t funds available for these innovative pilot projects. Glenn Burleigh, for example, has been talking until he’s blue in the face about a high loan to value fund that will help address some of the issues with properties that are dilapidated. Imagine you’re lending money that’s over what the value of the home is. If you can buy the property for $10,000, but it needs $100,000 worth of work, there’s not a bank that will loan you money for that to rehab. So there’s a program in Detroit that’s been doing this that has been very successful. And we’re trying to pull that project together in St. Louis through SLEHCRA. So a fund to address really specific racial disparities that could provide action-oriented outcomes to address some of the calls to action would be a good thing.

Jacqueline Hutchinson (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Jackie: Back to Elisabeth’s point, there is a lot of organizing and educating that needs to be done. There are still a lot of people in the city that don’t even know the work that we’re doing or how it impacts them. Though some banks are doing a pretty good job, they’re not able to get the word out in the way that it needs to. Sometimes it takes smaller groups to do it. You can’t just say, “Well, the bank has got these loans, you can put money in this bank, then you can get a loan from this bank.” All of those things go over people’s heads because they don’t believe it. They often say, “That doesn’t apply to me because the banks never have loaned Black folks money.” An example is in my own family.

I was at a family dinner and my sister said she needed money for a new water heater and plumbing. I said, “You know you can go to the bank and get a loan for $5,000 at 1.99% interest.” She said, “Why would they loan me money? Why would they loan me money that cheap? I’m not going to the banks so they can deny me.” I kept saying, “Look, just call them up and apply for the loan.” We had this big argument. Finally, I said, “I’ve been doing this work for the last six years, so you can go in the bank and get you some money. Go to the bank.” She went to the bank and got the loan. She knows that I’m doing work around lending and banking. She didn’t believe that it applied to her until she went to the bank and got a loan. She later got her house refinanced at another partner bank.

You wouldn’t believe the number of people who just don’t believe that they would be greeted in a bank if they go in, and the treatment that some of them anticipate getting historically based on interactions in banks. The bank can advertise all they want. Unless there’s a community partner, like Friendly Temple Church next door to this bank, or Community Action Agency, or EHOC, or SLEHCRA, saying this bank is a good partner and talking to them in small groups so that they really do understand that it applies to them, they won’t necessarily know. Because when you read it in the newspaper, you think it applies to somebody else and not necessarily you.

How can other folks be thinking courageously about building Racial Equity into what they do?

Jackie: It’s difficult to get organizations to commit the time, particularly organizations whose job it is to provide those day-to-day services. So the conversation has to change to focus on the community benefits of the work, how much impact there is, and how much long-term impact there is. If you get one family to buy a house that otherwise wouldn’t buy a house, or if you get one family to open up a bank account and that leads them to be able to get a loan to repair something and then later on to buy a house, think about how much those kinds of things impact the community. The work has to be done within organizations to refocus the attention. Yeah, we do have to make sure that people have immediate shelter and food, but look how much impact there is if we devote resources to doing this community benefits work. Look how much more we can accomplish and give to the community as a whole.

If we’re working in a neighborhood, like this one – and let’s just go with people being able to repair their homes – a lot of homes in this area are generationally owned by African Americans, but they’re falling on disrepair. When your neighbor fixes their roof and front porch, now that’s motivating you to fix your front porch. And, pretty soon, you have a block that’s better and there’s economic development in the community. Somebody starts a store or builds a recreational center, or whatever it is, and the whole community is going to eventually move to a different place and be more economically sustainable. Then maybe people who live in South County might see an opportunity to buy a house in that community, and fix it up, and get their friends to buy a house in that community. So, the whole community could benefit from just having access to banking and loans. That’s how communities are rebuilt – by having the resources to begin by bringing in new housing, or new business and restaurants, and all those kinds of things follow.

Elisabeth Risch (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Elisabeth: Even more, we talk about credit and access to credit. Maybe that might mean that somebody has access to repair their roof or get a water heater. Or somebody on that block has access to buy a home that’s been vacant for three years and fix it up. It means that the property values in that area start to increase, too, and so that attracts other types of investment. Making sure that banks are lending fairly and equitably helps a whole neighborhood, not just an individual family that’s buying a home. Because the values as w whole respond back to the market.

My advice for other organizations and institutions is to not be afraid to change the status quo and shake things up a little. When we started doing this work, and even now, it became more about advocacy. It’s questioning things from institutional culture that has been in practice for so long at banks and at financial institutions. It a big risk to engage in that work and change how some banks are operating. It’s similar to the challenge of how development projects happen in St. Louis and asking for community benefit agreements. For that, especially in projects that are receiving tax subsidies, our money is going to subsidies projects and our community should have a say in what benefits those provide. The residents and community members that are coming into the neighborhood and the people that live in the surrounding area should be the ones negotiating and leading this process of demanding and asking for what they want. That is not the status quo of how we do things in St. Louis now, and it’s important that there are organizations and people asking questions and making sure that the status quo doesn’t happen anymore.

What’s the biggest shift in a policy that you’ve been really proud of?

Elisabeth: I’m proud that we can say we helped contribute to this new bank branch. They started off very poorly, and through years of work, through us figuring out how this process works and learning the nitty-gritty of the CRA and how you can use it and what the different banking regulations are, it’s really allowed us to push those buttons to create a bank in Pagedale that’s welcoming and inclusive. It’s about investing in communities that have historically not had investments here. They opened this branch and they have good people working for them that know how to meet people where they’re at to get them whatever kind of loan they need. We helped contribute to all these new families that are able to get loans and buy houses because of the little comment letter that we sent 10 years ago.

Jackie: So, we have to look at the $1.8 billion community benefits agreement by Enterprise Bank. They came to us and said they wanted to merge with another bank and would like to enter into a voluntary community benefits agreement. They’re not the first bank to do this, but we negotiated the largest community benefits agreement with them and the process was empowering. I won’t say we made demands, but we certainly had our list of things that we wanted and we held to that as much as we could. There were things that we knew were going to be deal-breakers, and others we compromised on. We brought in partners from Kansas City because the bank had branches in Kansas City. And it symbolized the cooperative nature of us negotiating something that we didn’t have to go and file a Justice Of Department complaint for or any of that. They voluntarily came to us and said, “Hey, we want to do this merger and we would like to negotiate with you also.”

It was fantastic and very empowering because they knew going into it that we could interrupt, maybe not stop, but certainly interrupt their plans to merge. They were smarter than some of the other banks. They learned that it would be better to sit down with us cooperatively. And we learned that some of our folks at the table didn’t necessarily want to compromise. As a group, we had to build a consensus and to all compromise. It was a good process and the bank and our group came out learning some things about each other and also with a collaborative agreement that we both worked really hard on.

Elisabeth Risch (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

What’s the thing that you wish people would know about the work you do that they don’t really know?

Elisabeth: Redlining and lending discrimination still happens in St. Louis. Data and maps paint a really clear picture. It’s not a thing of the past and there are things that you can do about it. So if someone is denied a mortgage loan because their race has something to do with it, then there are things we can do about that. If the community is upset that there’s not a bank branch in their neighborhood, there are things we can do about it. So it’s still going on, but all hope is not lost. A lot of people figure they don’t know what to do. “We were denied a mortgage loan or there are just no bank branches.” No, call us and let’s talk. Let’s figure out what’s available to us and what are the options because we can help.

Jackie: The other piece of that is that it’s not as bad as it has been. We’re making some progress. I’m still disturbed by the numbers, but the first step is to have an institution like this bank in a community and to get people accustomed to walking through the door to get information. They have products that don’t require you to have a 700 credit score. There were banks that didn’t have home improvement loans, certainly not at 1.99% interest. Right here you can get one. So, there are options. We’ve made great first steps and we should take credit for those. We’re telling the banks what our community needs, and some of them are listening and they’re coming up with products that meet the needs. When we meet with the banks, and they’ve developed products but they haven’t taken that step to where they’re marketing them in the way that they need to, we ask, “Where are you advertising that product?” They need to make people really believe, one, that it exists and, two, that if you walk into that bank, you can get that loan. There’s a lot more work to be done and a lot more for us to do.

Jackie: Elisabeth should send you a picture of us standing on a vacant lot on the corner of Martin Luther King Dr. when she said, “There’s not a bank from here to downtown.”

Photo courtesy of Elisabeth Risch.

Elisabeth: We like to stage some of our events in places that we think need to have bank branches. That corner is still not a bank branch.

Jackie: Yeah, there’s not a bank branch there, but we’ve got this one here.

Jacqueline Hutchinson

Board President for Consumers Council of Missouri and Co-Chair of SLEHCRA

Elisabeth Risch

Assistant Director of EHOC and Co-Chair of SLEHCRA

#FwdThruFerguson