This is part of the #STL2039 Action Plan storytelling series in partnership with Humans of St. Louis.

Amelia Bond: The St. Louis Community Foundation was founded about 100 years ago in 1915. It was the second oldest community foundation in the country next to Cleveland’s. And the concept from its origins was to promote philanthropy to have a more vibrant St. Louis. Back then, people would pass away and they would give their money away and endow it for the future. It took The Community Foundation a long time to get off the ground here for a whole host of historical reasons, but in the mid- to late 80s, civic progress said, “We need a community foundation.” Lo and behold, we have one and it has evolved to what we are today, which is a place for donors who tend to be high net worth individuals, who have assets, and they’re charitably inclined. They want to give back to their community. Our whole purpose is to speak to the endowment. And St. Louis, quite frankly, is not particularly good at endowing itself.

It’s only in recent years that organizations have started to realize they need an endowment to be sustainable.

We’re all used to annual giving, but it’s only in recent years that organizations have started to realize they need an endowment to be sustainable. Higher ed institutions have always been good at endowment building. Washington University is a great example. Forest Park just completed their endowment and ended up with about $130 million. And I remember meeting years ago with Brent Benjamin, who runs the Art Museum, part of the Zoological Park and Museum District, and he said because of the Zoo-Museum District tax, that they’re running the Art Museum as if it had a half a billion dollar endowment. But it’s not an endowment, it’s a tax. When there was the uproar over the History Museum and their investment in some land, there was a lot of discussion about, “Should we repeal the tax?” And that was frightening because these key cultural institutions in St. Louis rely on that tax. But taxes can come and go. Endowments really create security and sustainability.

During the last 100 years, donors have evolved, too. Community foundations created what’s called a donor advised fund back in the mid-’50s. Well, that’s become the most popular vehicle for donors to give. Here at the Foundation we hold 650 different funds. About 70 percent of those are donor advised funds. Those are living, breathing donors that either made the wealth for themselves and then made a charitable contribution to create a fund or their children are the advisors. It can go on for generations.

So we provide all kinds of services to donors and they’re doing grantmaking for initiatives in the community. About 85 percent of their grantmaking stays in St. Louis. The other 30 or 40 percent are endowed either where a donor has told us what to do, like, “Every year I want the earnings off my perpetual fund to go to the Art Museum.” Or, we have a wonderful old fund by Lucille Papendick. She was South City, very modest means, no children. When she died, she left her legacy here. And it’s a field of interest funds where Lucille said, “I want to give forever to the children in education and in the arts.” And she left it up to The Community Foundation to figure out what’s that need this year. So, each year, to fulfill her wishes, we decide where that money should go in our region. It’s so cool because every year we talk about Lucille and where did Lucille give? We have a couple of handfuls of that type of fund, and we should have thousands.

Last year, $80 million went out of The Community Foundation in grantmaking to nonprofits.

We’re constantly trying to tell these stories to donors, and the stories that are embedded among these donors, about what they do in St. Louis and where they give and why they give. And their passions are awesome. Of 650 funds today, our total asset base is about a half a billion dollars. We’ve tripled in size in the last six years. Last year, $80 million went out of The Community Foundation in grantmaking to nonprofits. An enormous percentage of that is what we call donor directed or donor recommended. So we hope we try to provide whatever type of assistance a donor needs.

Amelia Bond and Maria Bradford. (Photo story by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis.)

Maria Bradford: Speaking to the areas that you’re asking us about, we also have programs that we run out of The Community Foundation to support things that are going to benefit the community broadly. We have fiscal sponsorships, which are programs that have the potential either to grow and become a stand-alone nonprofit organization themselves or, perhaps because of the way they are structured, it’s a collaborative program that fits really well with what we want to do in the community. So we have them here as part of The Community Foundation in perpetuity. STL Youth Jobs, for instance, currently runs out of here as a fiscal sponsorship and they provide summer employment to young people in underserved areas in St. Louis. They have very specific geographic areas that they’re targeting – Ferguson, Florissant, North City – and this is one of the things that blossomed with everything that happened after Mike Brown’s death. Like, one of the things that needed to happen was that young people need jobs. And there aren’t jobs for young people in St. Louis. So STL Youth Jobs started five years ago.

Amelia: And we were a co-founder with The Incarnate Word and Mayor Slay’s office. The project was to get youth off the streets in some of the worst neighborhoods in the city and give them an opportunity to work. There’s an intermediary and they have counselors that work with the kids to teach them – How do you dress for work? Do you have enough spending money for the first month to get on the bus to get to your job? – all those details. It’s much more complicated than just: You’re 18 to 24. You don’t have a car and you’ve never ridden from North City to somewhere in the county. To take a bus, how do you get there? So last year they had over 650 students that were employed. And it’s now a nonprofit that’s approaching a $2,000,000 operating budget. Their two employees are employees from The Community Foundation and they’re about to be their own nonprofit.

Maria: They’re leaving the nest, although they will always be a part of us.

Amelia: We love telling the story about them. So, if you think about it, in The Community Foundation, the donors are the community. We’re a very neutral place. We’re not political, we’re charitable. On one hand, we’re working to tell everyone how you can give. We have estate planning, gift planning, and wealth advisors because largely tax deduction is driving the charitable giving. So we’re out there promoting: give, give, give. We’re capturing it. And then we’re helping donors give it out.

Maria: We want them to know the how and we want to help them with the why as well.

Amelia: I spent 30 years in the securities industry. So, when I was brand new here, I had no street cred. I was just an old investment banker. I met Bridget Flood who runs The Incarnate Word Foundation, and at the time, there was a lot of youth crime and violence. We were going to youth violence meeting after youth violence meeting, and Bridget said, “Just shoot me. We’re not doing anything. We’re just meeting,” which is often the challenge in the nonprofit sector, right? How do we get things done? Bridget’s a doer, which is why I align myself with her. So she said, “I know one thing. I can figure out how to get these kids jobs.” We started talking and she said, “Let’s start the fund at The Community Foundation. We need to raise some money. It’s going to cost $2,500 per kid. We’ll go to corporations. We’ll go to donors. They can help one kid or they can help five or 10.” So it’s grown, as you can imagine, $2,500 at a time. We’ve got some major corporations that have given. The city uses the Prop S funds; that’s $100,000 dollars. And we were there when it started, which shows our connectivity to the community and our ability to implement something with other partners. We tell it to all of our donors.

Maria: Our donors know that this is a safe space for them and that we’re not going to be soliciting them for gifts. But we will be educating them about what’s going on in the nonprofit community, in the community at large, and talking about who’s doing really good work. They can always call us up and say, “I’m really interested in this, but I don’t know what the good things are. Can you help me?” And we will help them.

Amelia: STL Youth Jobs is an example of The Community Foundation’s work and it’s a program all about Racial Equity. It’s about how do we get kids jobs so they learn the skills at a young age to then say, “I know how to go on that next interview.” We’re not going to get equity until all kids get the opportunity to have jobs. That’s where the skill is learned.

Maria: They had their annual breakfast for some of their supporters in our building and employers talked about how STL Youth Jobs youth had impacted them. Then, several of the youth from, North County and from the poorest areas of the city, got up and talked about the impact that going through the program had on them. This summer, they’re trying to help 750 youth. The only limiting factor for how many kids they can get jobs for is how much money they can raise. There are thousands and thousands of kids who could take advantage of this program if the money was there.

Amelia: At that breakfast, there was a young woman presenting to all these donors. We probably had 50 or 60 people downstairs in that room. She was all dressed up and had worked at BJC that summer. She was young and has a baby. And she talked about what she learned in the job and the friendships and support system she built. She said, “Just to even have that job and getting there was complicated.” And it really was about the support system. So I’m standing next to Hillary who’s the executive director of STL Youth Jobs, and she said, “I told her to bring her resume because so and so from BJC, which is one of the largest employers in the region, is speaking today.” So we’re standing in the doorway and the event ends and I’m like, “Hillary, look! She’s pulling her resume out of her purse.” And it was so cool! I mean, that’s networking.

Maria: Earlier this week, I was out visiting one of the STL Youth Jobs sites in Ferguson – a pet groomers. And this small business owner had this young man that he hired through the program and he had participated every year. And the young man was no longer a participant in STL Youth Jobs, but an employee at Paw Perfect. In addition to that, he’s now graduated from high school. When he started the program, he didn’t know what he wanted to do. He just knew he kind of liked animals. So they matched him up with this pet groomer and now he’s at community college working towards getting a business degree. He wants to be a small business owner himself. So he had this whole experience of being mentored and seeing the ability to go and do something himself, which is what the whole program is about.

Amelia: In the first few years of the program, there was this boy who got a summer job in a mortuary. And he decided by the end of the summer that he was going to be a mortician. He wore his bow tie and was so charming. I would not be surprised if he was still there now.

Maria: That is a very respected business in the African American community. Being a funeral director and being in the funeral business, they are there at times when families really need someone to be there and be supportive. It’s a great career path.

Amelia: We have a couple of other initiatives and programs that fall into this space of the work of The Community Foundation that aligns with the Ferguson Commission’s report, too. St. Louis Graduates is a collaborative that started seven or eight years ago. It started with Civic Progress, The Scholarship Foundation, and The Community Foundation. And it was a way to work toward Racial Equity by establishing funding for college. We’ve got to find funding for college and, specifically, for the kids that are the underserved population of this community. We offer scholarships and that was a way to grow our scholarships as well as get students access. One of the initial ideas was to create Scholarship Central, an online portal where both organizations post all of our scholarships so kids have easy access to find them. And it’s an open architecture, so any organization that wants to post their scholarships there can. That is completely housed out of The Community Foundation.

Maria: One of the things that they’re talking about that they’d like to add is a college counseling resource center. A lot of our school districts don’t have college counselors, especially those that are in communities that are already underserved. They don’t have the financial wherewithal to have college counselors or, if they do, they have one for the entire district. There’s no way they can give the kind of quality and guidance.

Amelia: It’s finding that school that’s the right fit for the student and being informed. And, yet, being able to see a student that has some potential and helping to guide them to the perfect place would never cross their path. But St. Louis Graduates hopes to maybe someday find it. They have two employees upstairs, so they’re housed out of this building. It’s a collective collaborative group. There are about 20 nonprofits that are all part of this space, including Wyman and College Bound, so everyone’s pulling together to figure out, how do we raise the high-school and college graduation rates in the region? They set a goal initially at 50 percent. We were under 32 percent when they started. And, a year ago, they raised it to 63 percent. So they’re seeing progress.

One of the endowed funds here actually goes towards education. So that’s the connection of a donor with donor intent that endows our community and says, “How do we make a more vibrant region? And I want to do it through education.” “Well, we’re putting it in investing in this initiative to raise graduation rates.” Again, it’s very focused on the kids. How do we make it more equitable in our region? It’s through scholarships. It’s through access. We’ve got to get our high school and college graduation rates up.

How do we make it more equitable in our region? It’s through scholarships. It’s through access. We’ve got to get our high school and college graduation rates up.

Another community development initiative we have housed here is Invest STL. All of the players in the community development space realized that there wasn’t a central driving force. You have small community development organizations all over the region, all doing their own little piece, and there was nobody looking at the big picture. Invest STL is that organization that looks at the big picture and try to get dollars to help move the whole thing forward. Invest STL also realizes that small organizations are bubbling up from within neighborhoods. You can’t go in and tell neighborhoods what to do. It has to be organic and come from within. So one of the things that Invest STL is committed to doing is empowering those small organizations, and helping them grow and be strong enough that they can create their own processes to find out what it is that their neighborhoods need and want and then help them achieve those goals.

The federal government used to send a fair amount of millions of dollars to cities because it’s the neighborhoods in urban centers that were in distress. While the city used to divide it by ward, it’s not very effective because it’s not sustainable. Now people say, “It’s not rocket science. We know what needs to happen.” You need to have these strong community development agencies and then you need to get enough investment where people start to see the assessed values rise and part of the challenge is to avoid gentrification. But how do we prioritize those neighborhoods? We don’t have enough dollars to do everything. How do we pick a neighborhood where we can see success and then concentrate? And we don’t do that historically well here in St. Louis. The only reason that the West End has succeeded is because we had anchor institutions, like Wash U and BJC, who said they will change this neighborhood and sustain it. It had good housing stock and, while it had continued to decline, it was recoverable. But what about neighborhoods that don’t have an anchor institution? So Invest STL is a system and a collaborative between Wash U and UMSL and SLU.

And it’s to say, let’s find a way to fundraise at a bigger level because funding has dramatically declined, yet the need is bigger than ever. So if we can have a system that can, like us, along with others, say that this is a priority for our region, hopefully, we will have success to fundraise and then we can invest in and go through a selection process that picks neighborhoods through a priority system. Not saying we’re going to pick favorites, but we’re going to have who’s ready and where are we going to concentrate our dollars.

We’re talking to some of the neighborhoods that have seen the hardest decline. So it’s a direct correlation to the Ferguson Commission report. People live in places and it’s the housing stock, it’s the healthcare, it’s the transportation, it’s the education. So Invest STL can be that system that asks, “How do we connect all the nonprofit work, the fundraising that – at a larger level we hope we can do – and then have an impact on communities and work from within?” They have to want it. They have to be ready. We’re not going to tell these communities what to do. They’re going to tell us what they need to do, but we’re going to have the expertise. And that’s another thing, that St. Louis really doesn’t have is a lot of expertise in this area. And we want to leverage those pockets of where we have experts.

St. Louis really doesn’t have is a lot of expertise in this area. And we want to leverage those pockets of where we have experts.

Fifty percent of the donor-advised funds here have come in the last three years. The growth here in moving into this new building was like a change overnight. Prior to, offices were downtown on the third floor of the securities building next to the Federal Reserve Bank. No one knew we were there, which is why you don’t know much about us. Even Civic Progress who got us off the ground in the mid to late 80s, they don’t know who we are. But, last year we got our biggest fund ever – a $100 million fund. So as the community starts to see that the money’s here, this connectivity starts to take off.

Our biggest competition is commercial funds like Charles Schwab and Fidelity. Philanthropy is place-based. Eighty-five percent of the money stays here. We park our money for charitable purposes and donors do continue to make grants. Private foundations are required to give away five percent per year by law. That’s not a requirement of donor-advised funds. So, as an example, we started last year at $350 million, we ended the year at $500 million, and gave away $80 million. So we gave away nearly 20 percent last year. A lot of money went out of the foundation, and yet we grew by $150 million. Everything aligns with the Ferguson Commission Report because at the end of the day it’s about creating a more vibrant region.

Everything aligns with the Ferguson Commission Report because at the end of the day it’s about creating a more vibrant region.

You know, foundations often don’t talk to each other. Again, that’s why it’s so beautiful to have a community foundation because part of our job is to make sure donors are talking to each other. So we are trying to connect donors with each other, have events where they can connect, have learning sessions where they can connect, and that’s where you get the energy and you get people aligned to be more impactful. That’s why I came here six years ago. When I realized what a community foundation did and what this one was capable of doing, I was like, “This is a community imperative that we have a strong community foundation.” Us sending money to the Fidelities and Schwabs, we get none of these benefits. We charge fees and we’re more expensive than those firms. Wealth advisors always say, “You’re so expensive.” But 30 percent is going back into the community or into high touch service that our donors get. They don’t get the same service at Fidelity.

Maria: Which segues into someone who, although she’s not a donor, we hope that she will be. She called Amelia and said, “I’m interested in philanthropy, but what we’re doing here in St. Louis clearly isn’t working. I give every year. I give to organizations that I think I’m doing the right thing for, but I need to learn more.”

Amelia: She took it upon herself to say, “How do I learn more? How do I give differently so I can make a difference with regard to impacting Racial Equity.” Specifically. Quite frankly, this is an elderly lady in Ladue who said, “We’ve got to do stuff differently.” She’s very engaged in philanthropy. Her particular passion is conservation. So she came in here again and we said, “We’d be happy to meet you and be a resource.” We had a conversation. She described all that she was doing, and it was so impressive. She’s been going to the Ferguson Library participating in learning sessions and book clubs. She went to a couple of the Ferguson Commission meetings. And that’s what we need donors to do because you can imagine, here’s the rub – it’s a White privileged based donor base. That’s who donors are. It’s because we have had the inequity we’ve had. So we have to bring that donor base along to understand. And how are they going to understand? Certainly, getting language right. All these donors care a lot about St. Louis. They’ve made their money in St. Louis. They know they’re privileged. So how do they make a difference?

A hundred percent of our staff went through the anti-bias, anti-racist Crossroads workshop. We have to get the language right. This work is obviously hard. But if we can show them STL Youth Jobs, have conversations around Invest STL, have conversations around St. Louis Graduates – these are all initiatives that began to change the landscape where we’re, hopefully, having an impact. We need to look at grantmaking through a Racial Equity lens. “You, as a donor, need to look at your giving. We’d encourage you…” You know, using that language. As we grow, we get stronger. For example, we just hired someone in a new position and her sole purpose is to take the 10, 15, 20 largest donors here, depending on how many she can handle, and better the relationship we build with them and help them in their grantmaking. All the more able we have to make an influence on Racial Equity. All these donors care a lot about St. Louis. They’ve made their money in St. Louis. They know they’re privileged. So how do they make a difference?

To what extent is The Community Foundation connected to the Racial Equity Fund that Forward Through Ferguson is proposing?

Amelia: That’s a very interesting question. We have funds here at The Community Foundation and they’re individual donor funds. Donors may want to give to the Racial Equity Fund. I think it’s a challenge for Forward Through Ferguson and it’s a challenge for the region as to what’s that fund going to be used for and how’s it going to be used. Do you do it in terms of the work? Like, the various initiatives. And I’m not just talking about The Community Foundation initiatives. The United Way has initiatives. There’s other work going on by other organizations. You’re talking about an endowment for the work and who’s going to decide that? In other cities, that fund is a fund. It might not be called the Racial Equity Fund. It might be the Endowment of The Community Foundation, and then the board or the community foundation sets the agenda and says, “Racial Equity is a key.”

The problem is we have a society that hasn’t been equitable, and we know we have white privilege, and it needs to come from that population.

So, in this case, there’s been a lot of discussion about what should it be. The Ferguson Commission report obviously says to call it the Racial Equity Fund. There are those that say, “That’s the name it should have.” Others say, “Is that the name it should have? Should it be something different?” It’s not for us to decide. What does the community decide? The Community Foundation is very supportive of Racial Equity. We have some unrestricted funds. We don’t have a lot. Again, I’m sure we would participate. It’s more symbolic than anything else. Will donors give to it? That’s the answer I don’t know. That has been a struggle from what I hear.

And we talked about if the Racial Equity Fund should be held here. Obviously, I’m going to come from the perspective that I think so. That’s my own opinion and bias. Because who’s going to donate to that fund? The problem is we have a society that hasn’t been equitable, and we know we have white privilege, and it needs to come from that population. And then what structure is put in place to decide on that grantmaking? How do you communicate where that money’s going to be used and set parameters and framework around it? What’s the trusted institution so that population says, “I’m willing to give and I want to create this fund?” And who’s going to do that grantmaking and decision making? It doesn’t have to be here, but we’re that bridge and that’s our work. That’s our mission.

Maria: That’s what we’re all about. And we have the expertise in not only working with those donors and that donor population, but in helping put together structures around grantmaking that are quite varied and yet always professional because we work with several different foundations, and we do grantmaking, and provide that back-office support for several different private foundations.

What are the barriers to housing the Racial Equity Fund at the Community Foundation?

Amelia: One is how does it get off the ground funding-wise? Again, the donors make up The Community Foundation. As an organization, we don’t have an agenda other than a more vibrant region, of which clearly Racial Equity is key. And we’re apolitical. Now, there are those that might say, “Of course your political because you have this white donor base and we’re talking about a Racial Equity Fund and we don’t have it yet. So…?” So I would say politics is the biggest barrier. I think this is a trusted institution. It’s 100 years old. It’s growing at an extremely rapid rate right now.

Maria: We have the trust of the donors and the trust of the community that can support this fund. But in terms of Racial Equity in St. Louis, part of our problem is distrust. Because we are that institution of white privilege and we fully admit that.

Amelia: Although I’d put it differently. We’re not that institution of white privilege, but by the nature of the past, where the assets are held, and that’s the whole point of the Racial Equity Fund is to separate the two… It’s complicated.

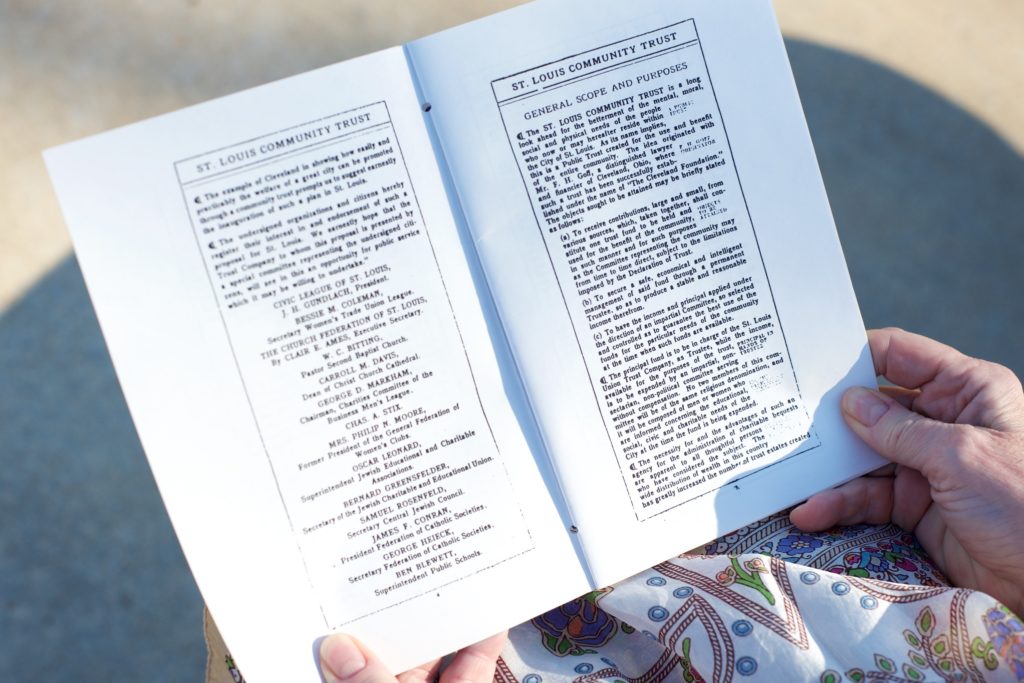

We have this wonderful little history book and the language of it is from 1915, and it’s beautiful, but it’s a hoot because it’s very old school. The Community Foundation was originally called The St. Louis Community Trust, and these are the letters and the original articles of incorporation. So it says, “St. Louis Community Trust is a long look ahead for the betterment of the mental, moral, social, and physical needs of the people who now or may hereafter reside within the city of St. Louis.” And it just goes on. I mean, some of the language too is so funny. It was an institution created to help the most in need in our region. That’s our history. That’s our purpose. And it’s going to come from those pockets of wealth. We are that bridge. So for the Racial Equity Fund, we’re the natural place to be that bridge. Will that happen? Will the fund get off the ground? Will it come to St. Louis? That’s not for me to decide. The region will either say it will be funded and it will most likely succeed if it’s place is here, or maybe they’ll say no.

What are the other options for where the Racial Equity Fund could potentially be placed?

Amelia: There are lots of organizations, us being one, that say, “We’re in this space. We want to put her brand around it. We’re so passionate about this.” The thing is, donor intent drives everything we do. We’re very entrepreneurial, innovative, and flexible because the only thing that guides us is the IRS code, grantmaking to 501(c)3s, and our bylaws. In my mind, that Racial Equity Fund is an endowment at The Community Foundation. Everything we’re doing and all those examples are really about solving neighborhood problems for where we experience poverty. It’s getting to the systemic problem, of which Racial Equity is by far the biggest. So whether it’s called the Racial Equity Fund or not, if this community foundation had an endowment, it would be going towards that. Now, Starsky Wilson would say, “But the work is Racial Equity. The work is not Invest STL. It is not.” I get that. So how do you put a structure around that so whoever that group is decides that that’s the way it should be? There’s a structure here that allows for that decision making and grantmaking. We support organizations that are advocates, but we are not a political entity. So we’re not going to fund particular campaigns. And the ability of that Racial Equity Fund depends on laws as well as opinions for how those funds.

Where else, who else has these donors with funds that have the assets and the means to be that catalyst to philanthropy?

We have some great examples of work being done that falls within certain areas of the Ferguson Commission report. There are so many aspects to it, but philanthropy plays a huge part as a catalyst. Where else, who else has these donors with funds that have the assets and the means to be that catalyst to philanthropy? And we are that hub. So we absolutely have to play a role in this. And we’re not perfect. I wish our board and staff had greater diversity. It is really important and I’ve learned a lot since I started. We are that beacon, so we have to be representative of the community. And that’s why I think if we don’t have the Racial Equity Fund here, it won’t happen. There’s no other organization like us. Maybe the Jewish Federation, and they have their religious cause whereas we’re agnostic.

Maria: And to illustrate the commitment of the organization, there’s that realization that we need to continue to educate ourselves on these issues. We need to continue to talk about these issues, internally and externally. When I was hired, I got an email the week before I started, “Oh, by the way, starting on Monday, there’s this two-and-a-half-day training, and we want you to go.” So my first day on the job, I was in anti-bias anti-racist training. Since then, everyone on our staff goes through it. And every time a small group of people from The Community Foundation goes to the training, we all get back together and talk about all of the things that we see in each of our own departments. That training was life-changing. In my primary role, I’m out meeting with nonprofits all the time and seeing what’s going on in the community. I learn about the organizations that are effectively addressing Racial Equity issues to be able to say to the people that I work with, for example, “You all need to know about this. We need to go visit Metro Market when they’re selling food at the Ferguson Community Center. We need to go see this.”

Amelia Bond and Maria Bradford. (Photo story by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis.)

Those are the sorts of interactions we have on a daily basis, but we all know that we still have to continually refresh ourselves with that. One of the things that we did – it is the tiniest of things, but it’s making a real difference for each of us individually – is that we started what I’m calling a book club. It’s not really a book club. But we get together once a month over lunch and we started it by asking, “Have we all read the Ferguson Report cover to cover?” We all pretty much said, “I’ve read this section. I’ve read that section.” So we’re going through the Ferguson Report section by section and we’re having a discussion about the community, where we are in the community this many years later, and where we are as an organization regarding each of those calls to action. We’re knowing that we need to keep this front and center in our minds, or else we might just get back to whatever it was we always used to do.

Amelia: At the end of the day, it’s so small and it’s what needs to be done. But if we can change our language and influence donors along the way, we’ll have our impact.

What is your vision for St. Louis in 2039, if it was a generation away from when Mike Brown happened?

Maria: It would be nice to be a few steps further along the path to be able to see that there is a pinprick of light at the end of that tunnel. That we are moving in the right direction. That the court system and all of those institutional entities, that for generations and generations before have perpetuated a racist society, are now changing and are realizing what true equity looks like. It’s been a lot more than one generation to set it all up. It’s going to take more than one generation to break it down. But to know that there is actual progress happening, that’s what I see in 2039. I see people being able to take a breath and say, “There is hope. There is progress.”

Amelia: A perfect world would be that we have crossed the Delmar Divide. That’s just a piece of it obviously. But there are two phrases I’ve heard along the way since Michael Brown’s death. “Change happens at the speed of trust.” Even with the Racial Equity Fund discussion we had, it’s about trust. It’s probably what’s knotting it all up is trust issues, which, of course, is understandable. So my vision for The Community Foundation is to be trusted and to be that bridge. We are sitting in the middle. We have one foot in that group that’s going to make a difference and be philanthropic catalysts. And I believe they care about St. Louis, passionately. And we have to expose them and teach them about the importance of Racial Equity. That it is a systemic problem to change. And the other thing is that I had a very moving event after Michael Brown’s death. And probably six or eight months later Starsky Wilson brought The Kellogg Foundation and a couple of other national foundations in and they had an event at Jazz at the Bistro. They put four or five panelists up on stage. And, I wasn’t a protestor. I can’t imagine. There are those people on the front lines, and it’s just not me. But I sat there listening to their stories and it was powerful. And they were all suffering, in my mind, from post-traumatic stress. And, Tory, this young man said, “I can’t fix 400 years in one day.” And then when I went to the anti-bias anti-racism training, I thought, “Now I understand those 400 years.”

Amelia Bond

President and CEO at The St. Louis Community Foundation

Maria Bradford

Director of Community Engagement at The St. Louis Community Foundation