This is part of the #STL2039 Action Plan storytelling series in partnership with Humans of St. Louis.

Valerie Patton: I’m the Senior Vice President of Inclusion and Talent Attraction and Executive Director of the St. Louis Business Diversity Initiative at the St. Louis Regional Chamber of Commerce. My work here at the Chamber is what I call life work. I’m a native St. Louisan. I’ve lived in DC and in Dallas, which means I’ve come home twice. But, growing up in St. Louis in the 60s and early 70s, you get a chance to see some of the things people talked about that happened in the 50s and the 40s and before. For me, it’s all about dignity and respect. It’s all about equity. I’m not so much about diversity anymore because that’s the easy piece. It’s the piece we can see. It’s the piece we can generally discern. So I’m big on equity and inclusion. How does a person have access to everything?

The young person that I am, I have seen a lot. My mother was from Miami and she migrated here through education. My father’s roots started in Arkansas and I was five when we went to see relatives there. We were going to Mr. Bob’s store and they said we had to go to the back of the store. I said, “I can’t do that.” I almost got everybody killed because I tend to be pretty outspoken. So to have those experiences and others, like going to the National Museum of African American History and Culture with my now 84-year-old mother who rode on those segregated rail cars displayed in there and she sat at the segregated lunch counter, so to be able to see that through her eyes… The whole equity and inclusion piece, it’s really important for me.

I went to St. Louis Public Schools from K-8th and Normandy High School from 9th-12th. I was the second class of African Americans to go to Normandy. When we moved into the area, there was a group of Black kids that grew up there, and we were looked at as outsiders. I made a conscious decision in the 11th grade that I did not want to do White people anymore because of the bullying, the taunting, and those things that go on. So to be able to experience and live through those barriers and then turn that into positive action and change is why I do the work today.

The work I’ve gotten paid to do the last 15 years is around diversity, and now inclusion and equity. First, we do multicultural leadership and talent development, which is a year-long leadership development program called The Fellows Program. We put it together to, hopefully, begin to level some of the playing field. The participants are nominated by their companies. They’re high-potential, high achievers. Generally, mid-career talent. So how do we get people out of the frozen middle and move them up? And how do we get them into assignments outside of the ones that seem to be carved out for people of color like HR and community relations? That program is my love, my baby, over 700 alum, and 12 years old going into its 13th year. And you see how you can really systematically changed things there in that work.

Second, we work with young professionals and the Regional Business Council. Now I’m spending a lot of time and energy around what we are calling diverse business solutions. Three years ago we acquired the Minority Business Council. It was in a state of needing to be rebuilt. That’s around equity and inclusion in the business arena. So through relationship building, through programming, how do we get the majority to recognize and use these companies without some of the excuses we hear, like, “They don’t have enough bonding in the construction world. They haven’t been in business long enough. They’re just not capable”? How do we change that? A lot of that’s going to be around relationship building.

And, third, some of the fun pieces are around talent. We do LouFest U, which is a regional college festival to get students to get engaged with St. Louis before they make those serious decisions about where they want to live, work, play, and invest. Also, with an initiative called the Global Leadership Forum, which is about getting multicultural talent building, sustaining, and growing diverse pipelines, we get folks interested in the STEM and STEAM arena. Then the second piece of that is, those organizations that are working in there, how do we get those to grow and sustain? I’m helping people as they relocate here, probably spending a little bit more time with people of color who are relocating here. A lot of stuff goes on in that world but, at the end of the day, it’s about dignity and respect. It’s around equity and inclusion. I could talk on and on about the work because we do a lot of work, but I hold up those three pillars.

St. Louis doesn’t have many problems that are different than any other major urban core.

As I’ve traveled the world, I realized that St. Louis doesn’t have many problems that are different than any other major urban core. I was just in Cleveland. St. Louis is north and south, and Cleveland is east and west. So how do you go about doing things differently? You have to be intentional and you’ve got to include people at that table to help make those decisions about how we’re going forward. I had a conversation with someone who said, “We can’t continue to do things top-down. We’ve got to learn how to take that grassroots initiative and turn it into something great.” We have the assets here. No question. It’s really about getting people engaged and involved who haven’t been before.

Valerie Patton and Greg Laposa. (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Greg Laposa: Valerie just shared a number of the key roles she has, but she’s also a mentor and teacher here at the Chamber. She’s taught me a lot since I’ve been here. When I came on board, I was coming from a teaching background as a high school English teacher and didn’t have a whole lot of experience in the Chamber world. I was particularly passionate around increasing educational opportunities in the region and wanting to look at that from more of a system, policy lens. I came on board and Valerie was one of the first to take me under her wing and give me a lot of good tips for assimilating into an organization that was completely different. There are some transferable things from teaching to here, but it’s certainly a different environment than being in a classroom.

I was a new project manager, which has a lot of connectivity to teaching, but it’s not the same. And, Valerie, having had that experience herself doing all the great things she’s done and growing as a leader, helped to impart wisdom on me. That’s shaped me. So I feel personally indebted to her for what she’s done for me since I’ve been here. Through that work, I got to work with Valerie on a number of projects related to the talent attraction work, and even some work around diverse business solutions that informed my perspective about what we can accomplish as a region if we’re good at bringing the right stakeholders to the table and making sure that we don’t always have to be the expert, but that we’re trusting the expertise of others throughout the community to help shape positive outcomes.

I’m focused on a larger initiative to see St. Louis become a top 10 region for educational attainment by 2025.

Now I’m the Vice President of Education Strategies, so I’m focused on a larger initiative to see St. Louis become a top 10 region for educational attainment by 2025. To that last point I made about collaboration and stakeholder input, that involves a lot of people across the St. Louis area working together in pursuit of a shared goal around seeing more people have access to the kinds of college and career readiness experiences that prepare them for post-secondary education and then supports them all the way through.

When I was a teacher, I wanted to get involved in education because I thought that education was the silver bullet to creating pathways to opportunity for people. I saw how much of an impact it had on my life in terms of being able to pursue post-secondary education and the opportunities that provided me. But it wasn’t until I joined this team and was working at the systems level to understand how education, while it’s one path that leads to opportunity, it’s within a bigger environmental context and it’s within a policy context. There are a lot of decisions made that influence outcomes for people that aren’t going to easily be solved by someone being able to pursue a post-secondary education. There are all kinds of policy decisions that either oppress or help people move throughout the economy. Working here, I’m looking at the region from that wider angle lens. Some of the work that’s been done by leaders in our community and understanding what the data shows, even for folks who have post-secondary education, there are still gaps. There are still disparities in economic opportunity despite higher education levels.

About 25 years out, what do we want St. Louis to look like?

That’s where it becomes imperative to look at things with a long view. About 25 years out, what do we want St. Louis to look like? And then making sure that we’re comprehensive in our approach because it’s not just education. It’s issues that impact economic opportunity and mobility that are not necessarily directly tied to things like education and job training. It’s also about transportation, childcare access, and housing policy. All those things create this environment in which people have the opportunity to thrive or determines whether or not they don’t. Growing up, I was fortunate and privileged throughout my life to have continuous levels of opportunity. You take that for granted when it’s your individual experience, unless you’re able to see how the bigger environment’s created and how it’s constructed over time.

I’m a history major, so I can appreciate how long it’s taken to solidify the kinds of systemic injustices that we have and how much work and persistence it requires for us to really dismantle structural racism. When you look at St. Louis, it’s always struck me how segregated it is. I grew up in South County, which is pretty White. With the Delmar Divide, there’s definitely a dividing line. And that segregation hurts people’s ability to be able to have shared experiences.

In St. Louis, like other cities, unless you’re being intentionally inclusive or unless there are leaders that are creating environments that encourage people being able to come together, you’re not going to be able to see the kind of results that we’re looking for in terms of Racial Equity. We need to have a bigger vision for what the region should be for all people. We have to look at how we dismantle some of the things that divide us, and segregation’s only one example of that. Segregation manifests itself in school districts and in other areas in the economy. So we have to be diligent in our approach to looking at a holistic way of tackling these issues.

This work of the St. Louis Regional Education Commitment, which was a project I worked on last year with a bunch of partners in higher education, business, and workforce development, has me bringing some folks together because we need to improve educational opportunities for all and more pathways to post-secondary education and training. We’ve made sure that at the front and center of thinking about strategy was the Racial Equity lens and it’s the first guiding principle that’s articulated in this document that we’ve forged with all these leaders. This document’s meant to be the strategic plan for building a stronger talent development system in the region for the long-term future.

So if we’re looking at results and outcomes, rather than – to Valerie’s point, just diversity and inclusion in process alone – but looking at what the result will be, that may shape how we think about the strategy that we developed to actually achieve Racial Equity. It’s not just about a policy or practice that we instituted. It’s about looking at the outcomes long-term, and are there still gaps and disparities? And, if there are, then regardless of whatever diversity policy we may have or whatever policy our institutions of higher education may have, that encourages more diversity in our student population. If they’re not seeing the same kind of graduation rates, and they’re not seeing the same kind of post-secondary outcomes – likewise, if we’re not seeing our community partners focused on measuring that outcome – then we won’t see the future St. Louis that we want to see.

It is about looking at that as a principle to define the strategies that we develop, but then also fundamentally measuring how that principle is translated into the results that we measure five years out, 10 years out, 15 years out, 20 years out. It’s not enough just to get more people into post-secondary education if we still have these pronounced disparities among who’s completing college degrees and who’s not. When you look at the region right now in terms of college attainment rates, there’s still a very stark disparity with respect to who’s completing it and who’s not. And it falls along those racial lines.

Valerie: I have two and a half business degrees, I have a master’s in social work with an emphasis on social and economic development, and I’m also an accountant by profession. So Greg’s been talking about systems. We live and work and play in this one big system. And systems can be changed, but it generally takes time. So how does the system change? It changes today, because when I started my career there was no such thing as a personal computer. Now we have smart devices. Life itself is on a 30 or 35-year cycle. In the 60s, there was a lot of unrest. A lot of people wanted to use their voice. Some systems changed. Now we’re back into that cycle. We’re at the 30 or 35-year mark. So you hear change. Students walked out of school because of the violence that’s been going on in many of these high schools across the country. Women got all upset and wore a bunch of pink hats and marched. And some systems are changing.

When we talk about the system – we’re going to look at St Louis as a system – have some things changed over the course of my short lifetime? Absolutely. Have some things stayed the same? Absolutely. Have some things gotten a little worse? Absolutely. So when we start looking at the system breakdown – and this gets me in trouble all the time – I think race is an excuse, not a problem. So when we talk about Forward Through Ferguson, we talk about the incident that spurred that. Those incidents were happening all over the country. But what does it come down to in the system? Some people had their own value system, thoughts, and beliefs. And you have emotions you can’t control. But the system that was really broken there was the system around policing and justice. And there are people in all those systems. There have been some very poor decisions made in policing and justice. And we experience them every day.

Race is an excuse, not a problem.

We have leaders and some things that have changed. One, it was a bold move by the governor to put together the Commission. I had the opportunity to sit on one of the subgroups. We now have thoughtful people in place that have a different outlook and approach on policing and the justice system. But as Greg said, being the historian that he is, a lot of these things took years in the making. I was looking at 60 Minutes a couple of Sundays ago and they were talking about Germany and how they deal with their prisoners who have committed horrific crimes. They treat them like human beings. The ones who have done the most horrific things, they live in an apartment complex. And then others, who are still pretty much in the institution, spend a lot of time outdoors. If they’ve been on good behavior, they get weekend passes. So we have criminalized and demoralized those in our justice system. Are we really trying to reform or are we trying to make money? The new public safety director in the City of St. Louis came out of the judicial system and opened a school for kids that have been in the juvenile system to show them a different way.

So it takes people, it takes intention, and it takes opening your mind to the possibilities. I was having a conversation earlier today, and I said, “My 84-year-old mother who’s a retired social worker, I tease her all the time that she could find good in an ax murderer.” I’m not quite there yet. But what I do is anticipate the good. I think most people, 99 percent of them, really are for the good. Now, are they for self-good? Or are they for worldly good? I want to work for the greater good, to help people have better lives through transformation and change. The greater good is making sure that people are having access. People do have voice and the things that begin to create the state of equity. So if the trash trucks come by South City on their regular scheduled day, I need them to do the same thing in North City. Don’t tell me that once the trash trucks get to that side of town that they’re all broken down and can’t hold the capacity.

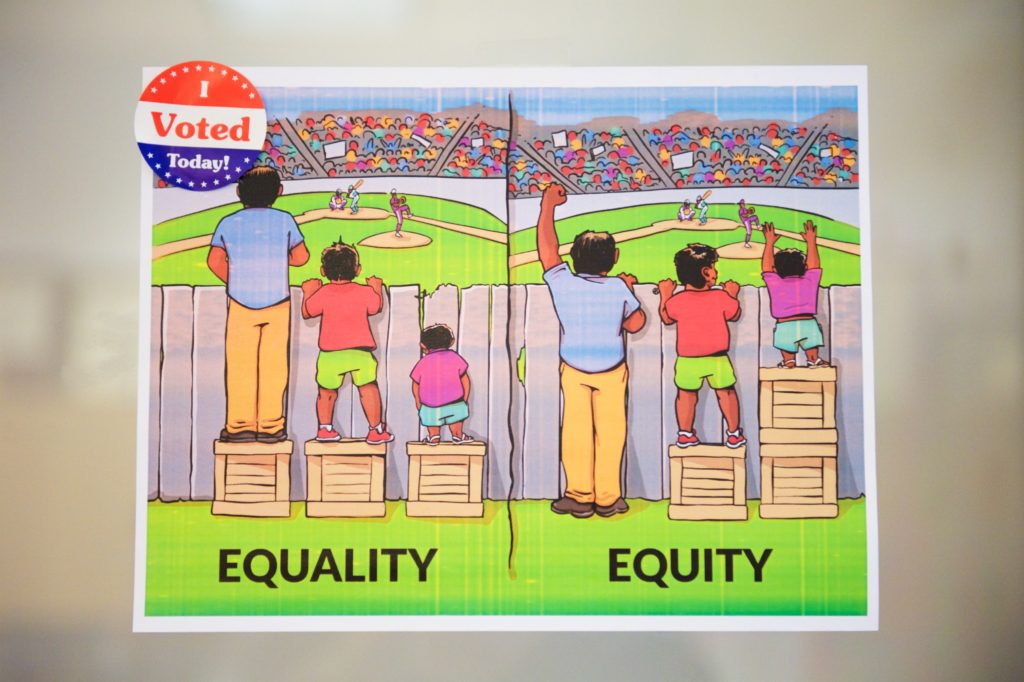

One of my favorite visuals is of three people going to a baseball game. It’s on our peer’s door. Equality is we all got to go to the game. Equity is everybody can see it. Now I don’t particularly like this example because there’s still the barrier called the fence. I got a better visual while I was in Cleveland, and it was about a housing community. So the one side shows broken windows and only one pipe for whatever services and that kind of stuff. Then on the other side, it has nice housing, it’s populated, and they have all the systems they need. Yeah, it does what it’s supposed to do. Everybody gets to see over the fence. But we now need to get rid of the fence. So whatever we have to make a great city greater is: whatever you’re doing in South City, you have to do it in North City.

On the Regional Chamber’s website, it says you want to, “Inspire a greater St. Louis.” How have you figured out how to put Racial Equity into your institution to be able to achieve this?

Valerie: We’re just at the beginning of really putting equity in it. We hire people, so we need to make sure those pools are diverse. We’re doing an okay job. We also have to learn how to understand and listen to everybody’s perspective, because what may have been your experience is not somebody else’s. We have this system called the Chamber. Some of us, because many of us are outward-facing, are forced to look at things from an equity point of view. Internally, though, we’ve started scratching the surface. We’ve got some work to do.

Greg: There are ways we’ve started talking more openly about applying a Racial Equity lens and that’s embedded in the commitment. The key point that Valerie’s making is that it’s not enough just to say this is important. It’s not enough just to do a training. And it’s not enough to just make sure that your hiring practices are more equitable. That work has to be consistently reinforced over the years and a longer period of time for it to fully become embedded deeply in the institution. I was fortunate to participate in the Crosswords Anti-Bias Anti-Racism training and what they helped me think through is that it’s not enough to talk about promoting that training and Racial Equity, but it’s also about being explicitly and intentionally anti-racist.

Be mindful of the fact that there are currently things you have to aggressively tackle and change.

When you look at institutions and our community, are we taking it to that level or are we just talking about new policies and practices or frameworks by which we’re looking at things? To really take it to the level of anti-racism, you have to be mindful of the fact that there are currently things you have to aggressively tackle and change. I agree with Valerie that we’re in the early stages as an organization. There have been a couple of projects here and there that have been advancing the calls to action in the Ferguson Commission’s report that are still in the early stages. The commitment being one and the work that we’re doing in education is one. And working on the Earned Income Tax Credit which is meant to help working families and address poverty as a core issue. I don’t know if chambers have traditionally gotten involved in looking at anti-poverty strategies, but that’s an example that our policy team has taken on. So there are examples of us making strides, but it’s in the early stages and we need to make sure that it’s consistently reinforced over and over because it’s easy to fall back on old ways if you’re not being intentional about creating new paths and sticking to them.

What are other ways you and the team have been able to prioritize equity in your work or where would you like to see it prioritized?

Valerie: That’s an unfair question because it’s my work every day. As a kid, everybody thought I was going to be a lawyer because I was always the champion for that one person that couldn’t speak for themselves. My dad was known as Mr. Goodwill, and like I said, my mother could find good in an ax murderer. My maternal grandfather, because he could read and write, worked in a paint factory in Miami. And for the men to have dignity in the plant where he worked, he taught his coworkers how to write their names. So activism, social justice, equity, and inclusion are a fabric of who I am. I spent a lot of time in the principal’s office either defending myself or defending somebody that couldn’t defend themselves. But I always had that eye, probably sometimes to a fault, to know right or wrong. I like to see a lot more grey now and I’m glad that I do. I always asked a lot of questions, and “why?” is one of my favorite questions. Why is this happening? Why is this set of events going on? So it’s just kind of the fabric of who I am. Some call it chivalry, but I call it the right thing to do. Because if you’re walking into Bread Co. and somebody’s behind you, you should be holding the door. I don’t care what they look like. Now, do I fall off the wagon every now and then? Absolutely. I’m human.

I like the country. It’s good for when you need to get your head clear. But I’m an urban person. So, in Cleveland, I took an Uber from the airport into town because it was cold and I didn’t really know where I was going. It’s not a city I travel to regularly. Then I took the urban way back to the airport, which was a free trolley that put me in touch with the fabric and humans of Cleveland. So there was a man sitting next to me that was talking to himself and then there was the woman sitting across from me that had about a gazillion bags. Then there was the woman who wanted to have a conversation with me because she was like, “Ooh, that’s a big bag for work.” It was my travel bag, and she was trying to figure it out.

So that’s just the trolley that took me to the little train with two cars that took me to the airport. Then I really got the fabric of the city at 4:30 Eastern time because school was getting out. You had school kids, working kids, working adults. You had people with mental health issues. You had all of this on this track and it was about a 30-minute ride. So I saw that they have similar problems to what we have. You see all the homelessness. You see all the different flavors of the city within that half an hour of the trolley ride from the office to the airport. I could have sat there and been a snob and decided not to see it or take an Uber back to the airport – which I’m really glad I didn’t because once it gets out of the city, it runs along the highway, and it was bumper to bumper traffic. But, it was all about the fabric and everybody looked different.

A “hello” is not going to kill you. And other things are not going to kill you, which are just human things.

There were a couple of guys I wanted to talk to to say, “Why do you sit in the seat with your feet up on the seat?” That’s just a me thing. You couldn’t smoke on the train, but I was sitting next to a woman who smelled like she was smoking. I’m like, “Whew!” You would have thought she was really over there smoking. Then there were the kids getting on the train and they were into this and into that and the rap music. So you can sit there and act like you’re afraid of all that or you just kinda go with it. A “hello” is not going to kill you. And other things are not going to kill you, which are just human things. And that’s how you begin to shift. I’m not saying that you have to give every person a dollar that asks you for a dollar. But you have to be able to be empathetic. Empathy plays a big piece in this because there but for the grace of God go I. So I could be that homeless person on the corner because life is transitory. You don’t know what’s going to happen a minute from now. So I do try to immerse myself in the city, especially a city that I don’t travel too often, so I can get some flavor of what the city is.

How did that inspire you then to come back here and do the work you’re doing in St. Louis?

Valerie: One of my many mentors, Frankie Muse Freeman, who just recently passed at 101 years old, would always say to me and the others that she mentored, “There is still work to do.” The work is not done. It won’t be done when I decided to go sit on a lake and fish all day. There’s still work to be done to authentically use your voice, which means you might not have a lot of people that like you at the end of the day. But you have to authentically use your voice and you’ve got to have a little bit of fun along the way. You can do this work. I tell people that this is not grown and sexy work. This is really pretty isolating work because a lot of people don’t like what you’re saying. “You want me to come out of my one-mile radius of comfort to engage with folks I’ve ever engaged with before?” So systems work gets really convoluted at the end of the day because, “In this one-mile radius, I’ve got to come to somewhere that seems foreign to me? And I’m supposed to understand you, but you’re not supposed to understand me?” And that’s where we have to get to the point of being equitable also. Because I’m not discounting your story. I don’t need you to discount mine.

I didn’t have my grandparents’ story. I didn’t live my parents’ story. I’m living my own story. I’m pretty much in tune with what I like and don’t like, what I’m going to deal with and what I’m not going to deal with. And, generally, race has nothing to do with it. If you’re not a nice person, I don’t really care what color you are. You’re not nice. Now if you want to say, “I don’t like you because you are…” That’s your stuff, that’s not my stuff. And if you ask me, I will tell you, “I don’t like you because you’re not nice.” I tried to minimize my involvement with people that are not nice. That’s where we have to get, and that’s around relationship building and uncomfortable conversations.

Greg, before you worked at the Regional Chamber, and with Valerie, did you think about Racial Equity work to this extent and infusing it into the work you were doing?

Greg Laposa and Valerie Patton. (Photostory by Lindy Drew/Humans of St. Louis)

Greg: The way I looked at it was not at the systemic structural level. You may think about individual racism, like, observing people who demonstrate behavior that’s not racist must mean that maybe we’re moving past a racist society, right? But the reality is that even if individuals aren’t practicing racism overtly, that has not somehow changed the policies or the environmental conditions that are in place that continue to constrain people. You’re not going to solve segregation and housing policy easily, because that took years of federal policy that shaped what’s happened in St. Louis. And then St. Louis doubled down on that with restrictive covenants and other policies that were put in place to reinforce that system.

What I’ve gained an appreciation for is the ability of people to be catalysts to disrupt and to change racist structures.

What I’ve gained an appreciation for is the ability of people to be catalysts to disrupt and to change racist structures. Valerie’s pointing out, she’s been a catalyst, and Frankie Muse Freeman was an obvious catalyst. Individual acts of leadership are important, and if you can inspire others and work with others – even with a small group – to build community support, you can make a significant dent in challenging structural and systemic inequity. It requires a community to alter systems. But, as Valerie was speaking, I was also thinking about sustainability. And that’s what the Frankie Muse Freeman comment really speaks to, which is that there’s still work to do. That work is ongoing.

You have to be able to train other leaders. Valerie’s done it with the Fellows Program and other areas where she’s helped shape and mentor other leaders. And I think intentionally about, “Who are the leaders of the future that are going to need to carry the work on, beyond the folks who are currently leading it?” A lot of people when they see things like injustice, they want it to just go away. They want to solve it or they want to hide from it and pretend like it doesn’t exist. It’s either those two options. But it’s long work and it’s going to require a significant commitment on the part of a variety of people acting together in pursuit of a shared vision and disrupting and improving institutions, simultaneously. You’re not going to be able to easily tackle this one piece at a time.

This is a bigger system that you need more partners in, and individuals can’t change things alone.

So I’ve developed that appreciation since I’ve been here to look at the long view and also realize that this is an interconnected ecosystem here. You have a role to play as an individual, but you’ve also got to make sure that you’re bringing more people along. You’ve got to realize that this is a bigger system that you need more partners in, and that individuals can’t change things alone even if they have a good platform from which to act. It’s not individuals. It’s about people moving together to create change.

What’s the last thing that you celebrated when it came to moving Racial Equity forward here?

Valerie: It was in Cleveland, at a convening with 13 other large chamber individuals that do diversity inclusion, and equity work. I saw a different twist on how to do the work. So I’ve come back enthused and energized and full of all kinds of ideas. One of the better decisions I’ve made this year was to go there and participate. Everybody had to submit a problem they were having and then we took a deep dive into them. So you ask the probing questions and for solutions and, if you presented a problem, you had to sit and really listen to what this community of individuals was telling you around your issue.

We started off with Tim Ryan, who is the U.S. partner running PricewaterhouseCoopers, and he talked about diversity, inclusion, and equity, and why it was important for them to integrate it. He said, “Everybody at PricewaterhouseCoopers has to go to unconscious bias training. You can’t opt out.” Then they do some deeper dive things for people that they’re putting on leadership tracks. He said, “Was I a little scared? Did I have everybody backing me? No.” And then he said, “You can do it. And I still probably have people in my firm that don’t believe in what we do. But a part of this is also being very transparent.” It was really energizing for me to sit back and look at, what are we doing? How are we doing it? What can we do better? How can I collaborate better? How can I maybe not do more, but do more with what I have?

And at the end of it we said, “We talked a lot about D & I, but I don’t know if we talked as much about Racial Equity.” But we really did as we heard the stories. One that stands out to me the most came from DC. When I lived in DC, it was The Chocolate City. Not so much anymore. And the problem that was presented was, “We have all these people of color in positions of power, influence, and authority. But people of color are not getting any access to opportunity, which is creating quite a bit of inequity.” Everybody in the room was like, “Really?! That kind of problem in DC?” You would never think it. So it was really, really good to hear those other stories.

I would like to do something to replicate some of that work here in St. Louis for us to begin to move some things forward. It’s easy to say, “This is a problem.” But I tend to be solutions-driven. So when you come to me, which Greg would attest to, don’t come here and tell me you have a problem. If you don’t have a solution, don’t come because I’m not gonna entertain that. A solution doesn’t have to be one that works all the time either. Because if it doesn’t work, we can learn from it and we can move on. But you’ve got to make that extra effort. People still get back to the root of all of this because people have to help us move forward. You’ve got to be able to say, “It’s okay to take risks. It’s okay to make a mistake. It’s okay to say something stupid.” And you’ve got to be able to also say, “Yeah, that really was stupid.”

Greg: When Forward Through Ferguson convenes meetings, I’m always impressed by the energy and the sense of possibility among the people that participate in discussions in thinking about how we prioritize our work. The work of the Ferguson Commission was really inspiring. When you looked at how broad and far-reaching that group’s work was – and not just the commissioners, but the working groups that were formed, and the sense of possibility in those rooms to look at how we can create a different St. Louis, and the energy around that – like anything, it’s going to require more convening and more of those kinds of conversations in shared environments for people to start working towards solutions. I’m excited to see that Forward Through Ferguson has looked at prioritizing a set of areas that will get us to 2039. We’re going to start identifying the calls to action that we as a community can achieve if we work collectively.

“What gets monitored gets done.” So if the goal is Racial Equity, we have to figure out what the right metrics are.

One particular project that sticks out to me that is inspiring is the work that’s going on with the City of St. Louis that Nicole Hudson’s leading focused on the equity indicators and looking at how we measure equity. They brought a group of people together to look at, “What should we really be measuring to know that we’re truly moving towards equity?” Knowing that the City of St. Louis is working on a project that will enable us to start looking at metrics to know where we stand as a region in our pursuit of trying to achieve Racial Equity, that’s exactly the kind of outcome-oriented thinking that we need to define the vision we have and to measure success. I worked for a former principal who told us teachers all time, “What gets monitored gets done.” So if the goal is Racial Equity, we have to figure out what are the right metrics to know the leading indicators to help us know how we’re moving towards that goal.

What does a racially equitable St. Louis look like to you in 2039?

Valerie: When we’re not talking about it. We will have done the things that need to get done to make it an everyday part of life. Diversity, inclusion, equity – all of those things should be a part of the everyday fabric. That means that we’re going to have to put some wheels in motion. We’re going to have to get some elbows dirty, some knees skinned. We need to not be talking; we need to do. We need to be in the phase of execution. Because we talk, we talk, we talk; and we meet, we meet, we meet; and nothing gets done. We have a roadmap called the Ferguson Commission report. That has given us 189 charges. I’m not saying that we’ll have all of them done by 2039. But if we take the core essence of the report and put the time, talent, and treasures toward them, then we won’t be talking about it because it would be part of the fabric. For me, the word diversity now is defunct and overused and overbaked. The diversity piece is easy to recognize most days. When we talk about this work now, it’s really more about the inclusion and equity piece. In 2039, what makes St. Louis an even greater place is because all of us are able to contribute, all of us are able to have an opportunity to explore, and all of us have an opportunity to create the change we want to see.

Greg: The standard definition defined by the Ferguson Commission report says that outcomes will not be predicted by race. So what that looks like on a concrete level in the work that we’re doing around education, is that the pronounced gaps in college attainment rates wouldn’t exist. Those disparities would be eliminated. Right now, if you’re a student who’s White, you have twice the likelihood of being able to complete a college degree successfully in this region. You’d want to see that gap for attainment rates shrink between people of color and White students. The data should tell a story where it’s roughly similar outcomes, then you’ll know at that point that those disparities have been reduced. And you’d see fewer silos in this region. You’d see less fragmentation. You’d see less or no segregation. Imagining the possibility of what else that could look like, there’s less otherizing of people; less of, “I care about the children in my neighborhood and I care about my family,” and more of seeing, as Nicole Hudson once said, “All kids as our kids.” and as a community. It’s not having communities as fragmented as they are. That would be what success could look like in pursuing a more equitable future.

Valerie Patton

Senior Vice President of Inclusion and Talent Attraction and Executive Director of the St. Louis Business Diversity Initiative, St. Louis Regional Chamber of Commerce

Greg Laposa

Vice President of Education Strategies, St. Louis Regional Chamber of Commerce